From Diagnostics to Donkeys: Analytical Chemists Easing World Poverty

At SciX 2016 in Minneapolis, Minnesota, the Society for Applied Spectroscopy sponsored the special session “Analytical Chemists Easing World Poverty.” This session was founded in 2011 by SAS Past-President Diane Parry to highlight unmet measurement needs in developing nations. With the support of sponsors like the SAS, Spectroscopy magazine, and ChromAfrica, it has evolved into a popular session that examines a variety of topics ranging from technical solutions to instrumentation problems to cultural challenges of Westerners working in developing nations.

At SciX 2016 in Minneapolis, Minnesota, the Society for Applied Spectroscopy sponsored the special session “Analytical Chemists Easing World Poverty.” This session was founded in 2011 by SAS Past-President Diane Parry to highlight unmet measurement needs in developing nations. With the support of sponsors like the SAS, Spectroscopy magazine, and ChromAfrica, it has evolved into a popular session that examines a variety of topics ranging from technical solutions to instrumentation problems to cultural challenges of Westerners working in developing nations.

The 2016 session featured three speakers: Dr. Saad Bhamla of Stanford University, Dr. Merlin Bicking of ChromAfrica, and Dr. Simi Dube of the University of South Africa.

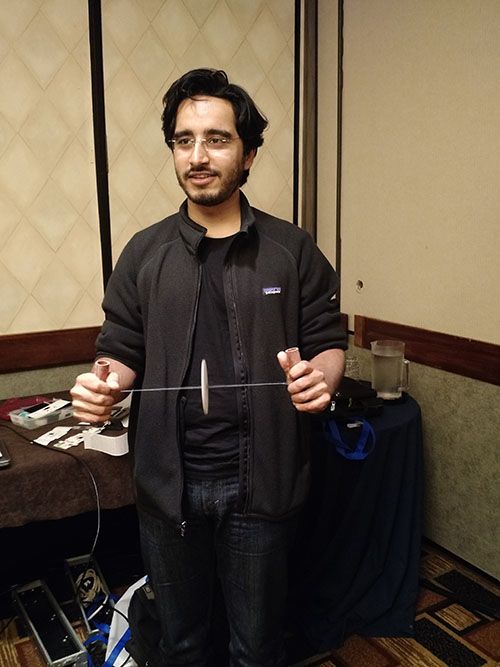

Bhamla is currently working in the lab of Dr. Manu Prakash at Stanford University. Their team is pushing the concept of “frugal science” to its boundaries from the perspective of engineering and physics, finding innovative and inexpensive methods to address measurement and diagnostic problems. Bhamla shared some of the fascinating solutions coming out of their lab. Access to stable power supplies is often a problem, so they have developed simple solutions to complex problems based on human mechanical power. A music box is used as a model for a hand-cranked microfluidics device (1) that can be used for bioassays and point-of-care diagnostics with no electricity. A sheet of die-cut paper is folded into a microscope (the “Foldscope”) that, with the addition of a simple ball lens, LED, and battery, can achieve bright-field resolutions of 2 µm, at a cost of less than fifty cents per microscope (2,3). Bhamla also shared some of the lab’s most recent work on a centrifuge device (the “Paperfuge”), based on an ancient spinning toy, that can reach 125,000 rpm with only human energy input (4). That’s 30,000g. The cost? Twenty cents.

Saad Bhamla demonstrates a prototype of the PaperFuge at SciX 2016.

During SciX, it was also announced that Prakash is one of the 2016 MacArthur Genius Grant Fellows (5), and Bhamla has been invited to speak again next year at SciX 2017 in Reno, Nevada, so we expect to continue to hear about this group’s work.

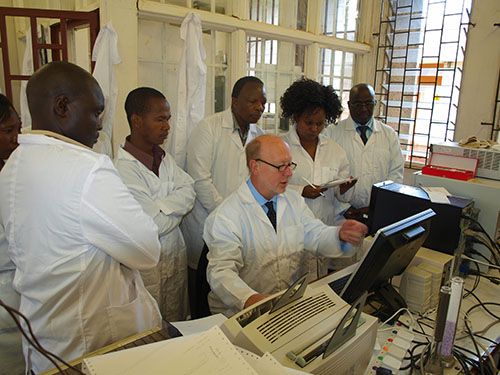

Merlin Bicking, a Minnesota native, didn’t have far to travel for SciX 2016, but he regularly travels to the other side of the globe to provide training and workshops to scientists in Kenya on analytical equipment, quality control, and regulatory issues. As the cofounder of ChromAfrica, Bicking works to address the lack of analytical instrumentation, replacement parts, and general training on the African continent (6). He spoke on the topic of instrumentation at SciX 2014 in Reno, Nevada. This year, he shared personal stories about the cultural barriers encountered in global business collaborations. A telling example involved a school on a hill, with a well a mile away. The school children spent so much time carrying water to the school that little time was left for actual learning. A German company stepped in and offered the school a solar-powered pump to drive water to the school. That worked temporarily, but the pump and solar panels were soon stolen. The German company provided a second setup, which was also stolen. Finally, someone thought to ask the people of the village what solution they wanted. What we need, they said, is a donkey and a cart. This donkey was valuable community property, which no one would think to steal. The school soon became one of the best in the area (7).

Merlin Bicking training a group of scientists at a ChromAfrica liquid chromatography method development workshop in Nairobi, Kenya.

Bicking emphasized the need to use indigenous knowledge and creativity to seek solutions collaboratively rather than imposing “Western” solutions on other cultures. African institutions don’t need more obsolete, donated spectrometers that can’t be used, he pointed out. They need access to funding and support that empowers local scientists and community members to creatively address African problems with African solutions.

Simi Dube, an associate professor of analytical chemistry at the University of South Africa, also spoke of the need to empower rather than impose. Scientists in Africa face a host of obstacles: Funding for science is almost nonexistent, power and internet access are unreliable, food scarcity is an ever-present threat, and many of Africa’s bright young people train in other parts of the world and never return (8). Women, however, tend to see education in terms of how it can help their communities, and women are empowering themselves through a variety of initiatives, including the Barefoot College (9). Dube described this program, which began in India and has spread to countries worldwide with the lowest socioeconomic indicators. It trains women, often considered in their communities as second-class citizens, to be engineers, teaching them to make solar lanterns (10). This skill is brought home and shared with others, providing essential light where often there was none, allowing children to study, adults to work, and economies to grow. Dube finds hope in such programs. “A woman who is empowered in the field of science is even better positioned to contribute in providing solutions to different kinds of challenges related to food safety and security, water quality and health,” she said (8).

This special session will continue next year at SciX 2017 in Reno, Nevada, under the umbrella of the new section “Contemporary Issues in Analytical Sciences,” which will bring together the existing special sessions on addressing world poverty, diversity and inclusiveness in STEM, educational innovations and initiatives, and the transition from graduate school to professional life. If you have ideas or suggestions for these sessions, please contact section chair Rebecca Airmet at Rebecca@AirmetEditing.com.

References

- G. Korir and M. Prakash, PLoS One, 10(3), e0115993 (2015).

- J.S. Cybulski, J. Clements, and M. Prakash, PLoS ONE9(6), e98781 (2014).

- C. Kormann, “Through the Looking Glass,” New Yorker, Dec. 21 & 28 (2015).

- M.S. Bhamla, B. Benson, C. Chai, G. Katsikis, A. Johri, and M. Prakash, “Paperfuge: An Ultra-Low Cost, Hand-Powered Centrifuge Inspired by the Mechanics of a Whirligig Toy,” bioRxiv 072207; doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/072207.

- MacArthur Foundation, “MacArthur Fellows Program, Meet the Class of 2016, Manu Prakash, Physical Biologist and Inventor,” MacFound.org (2016), available at https://www.macfound.org/fellows/965/.

- M. Bicking, “Merging Business, Science, and Culture in East Africa,” presented at SciX 2016, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2016.

- S. Dube, “The Role of a Woman in Science in Poverty Reduction: An African Perspective,” presented at SciX 2016, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2016.

- R.J. Nair, “Indian College Turns Rural Women into Engineers,” Barefoot College, March 1 (2015), available at https://www.barefootcollege.org/indian-college-turns-rural-women-into-engineers-2/.

- S. Desai, “India’s Barefoot College Lights Up the World,” Aljazeera, January 15 (2014), available at http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2014/01/india-barefoot-college-lights-up-world-201411464325362590.html. â

New Study Reveals Insights into Phenol’s Behavior in Ice

April 16th 2025A new study published in Spectrochimica Acta Part A by Dominik Heger and colleagues at Masaryk University reveals that phenol's photophysical properties change significantly when frozen, potentially enabling its breakdown by sunlight in icy environments.