Raman Spectroscopy

Have you used Raman spectroscopy? If not, you’re really missing out, and now is a great time to try. Raman spectroscopy has come a long way since its discovery in the 1920s. Named after the Indian scientist C. V. Raman, who won the 1930 Nobel Prize in physics, Raman spectroscopy had remained for a long time mostly a specialized tool only accessible to trained scientists. Since the early 2000s, however, advances in laser technology, fiber optics, and grating technology have come together to break down technology barriers and revolutionized and democratized Raman spectroscopy technology.

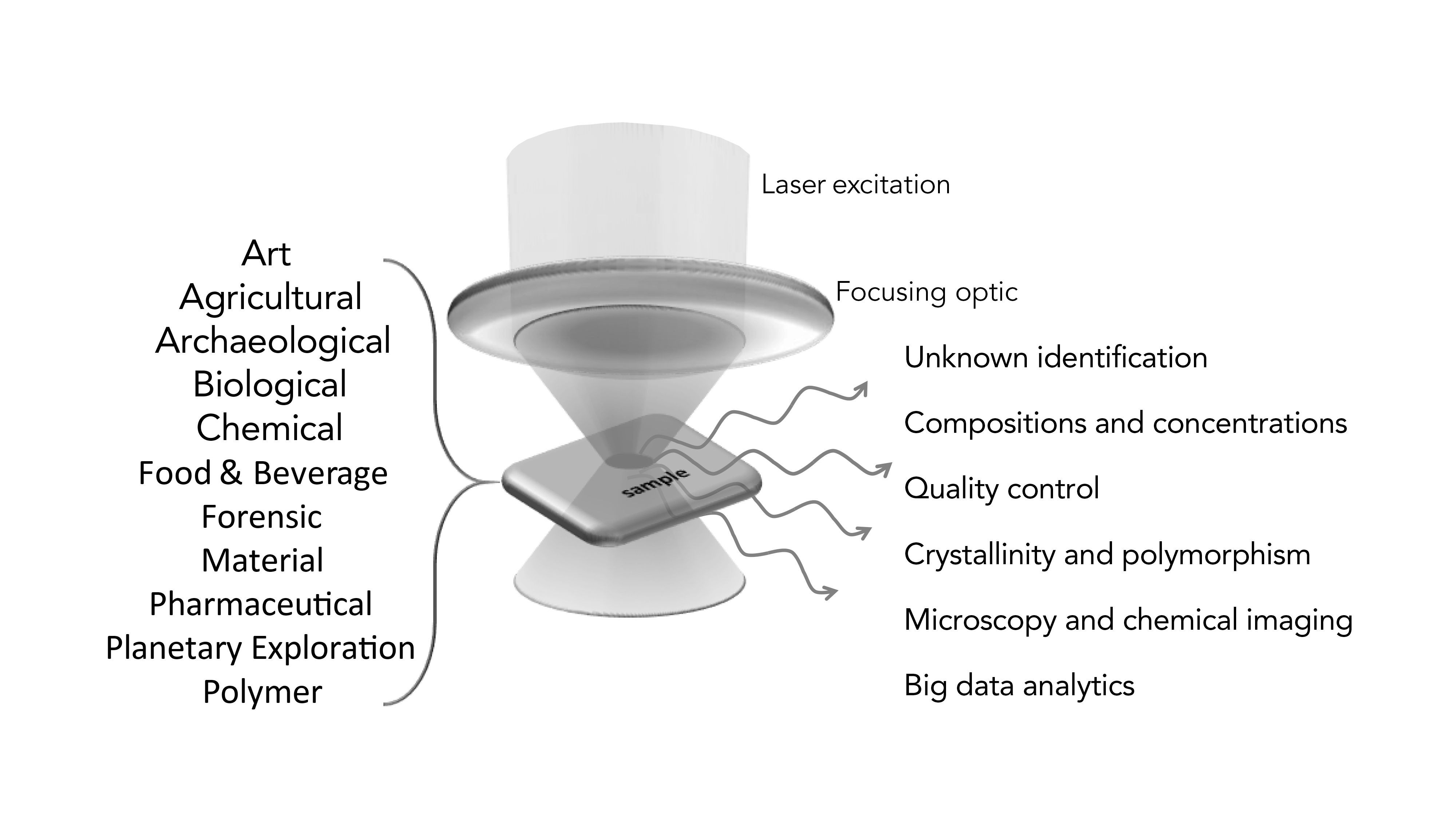

Most modern Raman spectroscopy instruments focus a laser beam to a tight focal point where Raman signals are generated. The back-scattered signals are then collected and dispersed using a grating onto a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera to generate Raman spectra. Such vibrational spectra contain information similar and complementary to that provided by infrared spectroscopy. The sampling mode in Raman spectroscopy is highly versatile, and can be achieved using microscopes or probes in both contact and non-contact fashion, and even in a remote-sensing setup. The development of these versatile sampling capabilities has enabled users to carry out many unique types of analysis not previously possible, such as the non-invasive analysis of historical paintings or archaeological artifacts.

Advances in chemometrics, big data, and artificial intelligence are now enabling maximum extraction of the rich information embedded in Raman spectra. Compared to separations-based analytical technologies such as gas chromatography (GC) and liquid chromatography (LC), chemical resolution by Raman spectroscopy is achieved through analyte spectral separation, rather than through physical separation of analytes via the use of separation columns. Analysis of convoluted spectra has often been a bottleneck in Raman spectroscopy, but this challenge is being addressed through the use of the abovementioned computational tools.

Figure 1: Raman spectroscopy has found its use in numerous fields (left column) and offers a wealth of analytical information (right column). The basic Raman measurement configuration is illustrated.

Raman spectroscopy has found its way into numerous application fields, a number of them shown in Figure 1. The reason behind such a wide range of successful applications stems from the robustness and versatility of modern Raman spectrometers, as well as the rich information available from the Raman spectra. Robust and miniaturized Raman instruments enable users to deploy Raman spectroscopy not only in everyday life, such as for the analysis of microplastics and the identification of unknown substances by law enforcement, but also in remote reaches of science, such as deployment on the Mars rover to study the geology of the red planet.

Numerous commercial options for portable and handheld Raman spectrometers are available. This range of options makes it a “buyers” market for users interested in exploring Raman spectroscopy for their own unique applications, but may also make it a daunting task to select the right tool. Interested readers are recommended to find expert opinions on such topics from professional organizations such as the Society for Applied Spectroscopy (https:// www.s-a-s.org/index.html) and the Coblentz Society (http://www.coblentz.org/).

Raman spectroscopy is a maturing technology, and there are many areas under active academic and industrial investigation. For example, surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) enables orders-of-magnitude improvements in detection limits. Spatially offset Raman scattering (SORS) allows chemical analysis of objects beneath opaque packages. Tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (TERS) overcomes the diffraction limit and offers chemical information with a spatial resolution on the order of tens of nanometers. From the nanoscale to microscopy to applications of handheld and portable instruments to analyzing industrial-scale reactions, Raman spectroscopy is a widely used and valuable analytical technique.

Xiaoyun (Shawn) Chen is with The Dow Chemical Company in Midland, Michigan.

AI-Powered SERS Spectroscopy Breakthrough Boosts Safety of Medicinal Food Products

April 16th 2025A new deep learning-enhanced spectroscopic platform—SERSome—developed by researchers in China and Finland, identifies medicinal and edible homologs (MEHs) with 98% accuracy. This innovation could revolutionize safety and quality control in the growing MEH market.

New Raman Spectroscopy Method Enhances Real-Time Monitoring Across Fermentation Processes

April 15th 2025Researchers at Delft University of Technology have developed a novel method using single compound spectra to enhance the transferability and accuracy of Raman spectroscopy models for real-time fermentation monitoring.

Nanometer-Scale Studies Using Tip Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy

February 8th 2013Volker Deckert, the winner of the 2013 Charles Mann Award, is advancing the use of tip enhanced Raman spectroscopy (TERS) to push the lateral resolution of vibrational spectroscopy well below the Abbe limit, to achieve single-molecule sensitivity. Because the tip can be moved with sub-nanometer precision, structural information with unmatched spatial resolution can be achieved without the need of specific labels.