Why Do We Need Quality Agreements?

In pharmaceutical contract manufacturing, the work of analytical scientists is covered by a quality agreement, which is prepared by personnel in the quality control or quality assurance department and focuses on the laboratory analyses provided. But what exactly are quality agreements, why do we need them, who should be involved in writing them, and what should they contain? Here, we answer those questions.

What are quality agreements, why do we need them, who should be involved with writing them, and what should they contain?

In May, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) published new draft guidance for industry entitled "Contract Manufacturing Arrangements for Drugs: Quality Agreements" (1). I just love the way the title rolls off the tongue, don't you? You may wonder what this has to do with spectroscopy or indeed an analytical laboratory, which is a fair question. The answer comes on page one of the document where it defines the term "manufacturing" to include processing, packing, holding, labeling, testing, and operations of the "Quality Unit." Ah, has the light bulb been turned on yet? Testing and operations of the quality unit — could these terms mean that a laboratory is involved? Yes, indeed.

Paddling across to the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, the European Union (EU) issued a new version of Chapter 7 of the good manufacturing practices (GMP) regulations that became effective on January 31, 2013 (2). The document was updated because of the need for revised guidance on the outsourcing of GMP regulated activities in light of the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) Q10 on pharmaceutical quality systems (3). The chapter title has been changed from "Contract Manufacture and Analysis" to "Outsourced Activities" to give a wider scope to the regulation, especially given the globalization of the pharmaceutical industry these days. You may also remember from an earlier "Focus on Quality" column (4) dealing with EU GMP Annex 11 on computerized systems (5) that agreements were needed with suppliers, consultants, and contractors for services. These agreements needed the scope of the service to be clearly stated and that the responsibilities of all parties be defined. At the end of clause 3.1 it was also stated that IT departments are analogous (5) — oh dear!

Also, ICH Q7, which is the application of GMP to active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), has section 16 entitled "Contract Manufacturing (Including Laboratories)." This document was issued as "Guidance for Industry" by the FDA (6) and is Part 2 of EU GMP (7). Section 16 states that "There should be a written and approved contract or formal agreement between a company and its contractors that defines in detail the GMP responsibilities, including the quality measures, of each party." As noted in the title of the chapter, the scope includes any contract laboratories, which means that there needs to be a contract or formal agreement for services performed for the API manufacturer or any third-party laboratory performing analyses on their behalf.

Therefore, what we discuss in this gripping installment of "Focus on Quality" is quality agreements, why they are important for laboratories, and what they should contain for contract analysis. The principles covered here should also be applicable to laboratories accredited to International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 17025 and also to third-party providers of services to regulated and quality laboratories.

What Are Quality Agreements?

According to the FDA, a quality agreement is a comprehensive written agreement that defines and establishes the obligations and responsibilities of the quality units of each of the parties involved in the contract manufacturing of drugs subject to GMP (1). The FDA makes the point that a quality agreement is not a business agreement covering the commercial terms and conditions of a contract, but is prepared by quality personnel and focuses only on the quality of the laboratory service being provided.

Note that a quality agreement does not absolve the contractor (typically a pharmaceutical company) from the responsibility and accountability of the work carried out. A contract laboratory should be viewed as an extension of the company's own facilities.

Why Do We Need Quality Agreements?

Put at its simplest, the purpose of a quality agreement is to manage the expectations of the two parties involved from the perspective of the quality of the work and the compliance with applicable regulations. Under the FDA there is no explicit regulation in 21 CFR 211 (8), but it is a regulatory expectation as discussed in the guidance (1).

In contrast, in Europe the requirement is not guidance but the law that defines what parties have to do when outsourcing activities as (2):

Any activity covered by the GMP Guide that is outsourced should be appropriately defined, agreed and controlled in order to avoid misunderstandings which could result in a product or operation of unsatisfactory quality. There must be a written Contract between the Contract Giver and the Contract Acceptor which clearly establishes the duties of each party. The Quality Management System of the Contract Giver must clearly state the way that the Qualified Person certifying each batch of product for release exercises his full responsibility.

Who Is Involved in a Quality Agreement? (Part I)

Typically, there will just be two parties to a quality agreement; these are defined as the contract giver (that is, the pharmaceutical company or sponsor) and the contract acceptor (contract laboratory) according to EU GMP (2). Alternatively, the FDA refers to "The Owner" and the "Contracted Facility" (1). Regardless of the names used, there are typically two parties involved in making a quality agreement unless, of course, you happen to be the Marx Brothers (the party of the first part, the party of the second part … the party of the 10th part, and so forth) (9).

If the contact acceptor is going to subcontract part of their work to a third party, then this must be included in the agreement — with the option of veto by the sponsor and the right of audit by the owner or the contracted facility.

Figure 1 shows condensed requirements of EU GMP Chapter 7 regarding the contract giver or owner and the contract acceptor or contracted facility to carry out the work. Responsibilities of the owner are outlined on the left-hand side of the figure and those of the contracted facility are outlined on the right-hand side of the diagram. The content of the contract or quality agreement is presented in the lower portion of the figure. These points will be discussed as we go through the remainder of this column.

Figure 1: Summary of EU GMP Chapter 7 requirements for outsourced activities.

What Should a Quality Agreement Contain?

According to the FDA (1), a quality agreement has the following sections as a minimum:

- Purpose or scope

- Terms (including effective date and termination clause)

- Responsibilities, including communication mechanisms and contacts

- Change control and revisions

- Dispute resolution

- Glossary

Although quality agreements can cover the whole range of pharmaceutical development and manufacturing, for the purposes of this column we will focus on the laboratory. In this discussion, the term laboratory will apply to a laboratory undertaking regulated analysis either during the research and development (R&D) or manufacturing phases of a drug product's life, including instances where the whole manufacturing and testing is outsourced to a contract manufacturing organization (CMO), the whole analysis is outsourced to a contract research organization (CRO) or testing laboratory, or just specialized assays are outsourced by a company. In fact, there are specific laboratory requirements that are discussed in the FDA guidance (1).

Scope

The scope of a quality agreement can cover one or more of the following compliance activities:

- Qualification, calibration, and maintenance of analytical instruments. It may be a requirement of the agreement n that only specified instruments are to be used for the owner's analysis.

- Validation of laboratory computerized systems.

- Validation or verification of analytical procedures under actual conditions of use. This will probably involve technology transfer, so the agreement will need to specify how this will be handled.

- Specifications to be used to pass or fail individual test results.

- Supply, handling, storage, preparation, and use of reference standards. For generic drugs, a United States Pharmacopeia (USP) or European Pharmacopoeia (EP) reference standard may be used, but for some ethical or R&D compounds the owner may supply reference substances for use by a contract laboratory.

- Handling, storage, preparation, and use of chemicals, reagents, and solutions.

- Receipt, analysis, and reporting of samples. These samples can be raw materials, in-process samples, finished goods, stability samples, and so on.

- Collection and management of laboratory records (for example, complete data) including electronic records (10) resulting from all of the above activities.

- Deviation management (for example, out-of-specification investigations) and corrective and preventative action plans (CAPA).

- Change control: specifying what can be changed by the laboratory and what changes need prior approval by the owner.

All activities under the scope of the quality agreement must be conducted to the applicable GMP regulations.

More Detail on Sections in a Quality Agreement

Now, I want to go into more detail about some selected sections of a quality agreement. I would like to emphasize that this is my selection and for a full picture readers should refer to the source guidance (1) or regulation (2).

Procedures and Specifications

In the majority of instances the owner or contract giver will supply their own analytical procedures and specifications for the contract laboratory to use. These will be specified in the quality agreement. Part of the quality agreement should also define who has the responsibility for updating any documents. If the owner updates any document within the scope of the agreement, then they have a duty to pass on the latest version and even offer training to the contract facility. To ensure consistency, the owner could require the contract laboratory to follow the owner's procedure for out-of-specification results.

Responsibilities

The responsibilities of the two groups signing the agreement will depend on the amount of work devolved to the contract laboratory and the degree of autonomy that will be allowed. For example, if a laboratory is used for carrying out one or two specialized tests rather than complete release testing, then the majority of the work will remain with the owner's quality unit. The latter will handle the release process and the majority of work. In contrast, when the whole package of work is devolved to a CMO, then the responsibilities will be greatly enlarged for the contract laboratory and communication of results, especially exceptions, will be of greater importance.

In any case, the communication process between the laboratory and the owner needs to be defined for routine, escalation, and emergency cases. How should the communication be achieved? The choices could be phone, fax, scanned documents, e-mail, on-line access to laboratory systems, or all of the above. However, it is no good having the communication processes defined as they will be operated by people, therefore analysts, quality assurance (QA) staff, and their deputies involved on both sides have to be nominated and understand their roles and responsibilities.

Communication also needs to define what happens in case of disputes that can be raised from either party. The agreement should document the mechanism for resolving disputes and, in the last resort, which country's legal system will be the beneficiary of the financial largesse of both organizations as they fight it out in the courts. Unsurprisingly, I'm in the camp with the great spectroscopist "Dick the Butcher" who said "The first thing we do, let's kill all the lawyers" (11).

Records of Complete Data

Just in case you missed it above, the contract laboratory must generate complete data as required by GMP for all work it undertakes. This will include both paper and electronic records that I discussed in an earlier "Focus on Quality" column (10). The FDA guidance makes it clear that the quality agreement must document how the requirement for "immediate retrieval" will be met by either the owner or the contract laboratory (1). Both types of records must be protected and managed over the record retention period.

Change Control

The agreement needs to specify which controlled and documented changes can be made by the contract laboratories with only the notification to the owner and those that need to be discussed, reviewed, and approved by the owner before they can be implemented. Of course, some changes, especially to validated methods or computerized systems, may require some or complete revalidation to occur, which in turn will create documentation of the activities.

Glossary

To reduce the possbility of any misunderstanding, a glossary that defines key words and abbreviations is an essential component of a quality agreement.

FDA Focus on Contract Laboratories

In the quality agreement guidance (1), the FDA makes the point that contract laboratories are subject to GMP regulations and discusses two specific scenarios. These are presented in overview here, please see the guidance for the full discussion.

Scenario 1: Responsibility for Data Integrity in Laboratory Records and Test Results

Here, the owner needs to audit the contract laboratory on a regular basis to assure themselves that the work carried out on their behalf is accurate, complete data are generated, and that the integrity of the records is maintained over the record retention period. This helps ensure that there will be no nasty surprises for the owner when the FDA drops in for a cozy fireside chat.

Scenario 2: Responsibilities for Method Validation Under Actual Conditions of Use

Here, a contract laboratory produces results that are often out of specification (OOS) and has inadequate laboratory investigations. The root cause of the problem is that the method has not been validated under actual conditions of use as required by 21 CFR 194(a)(2): The suitability of all testing methods used shall be verified under actual conditions of use (8).

Trust, But Verify: The Role of Auditing

As that great analytical chemist Ronald Reagan said, "trust but verify" (this is the English translation of a Russian proverb). Auditing is used before a quality agreement and confirms that the laboratory can undertake the work with a suitable quality system. Afterwards, when the analysis is on-going, auditing confirms that the work is being carried out to the required standards. Both the FDA and the EU require the owner or contract giver to audit facilities they entrust work to.

There are three types of audit that can be used:

- Initial audit: This audit assesses the contract laboratory's facilities, quality management system, analytical instrumentation and systems, staff organization and training records, and record keeping procedures. The main purpose of this audit is to determine if the laboratory is a suitable facility to work with. The placing of work with a laboratory may be dependent on the resolution of any major or critical findings found during this audit. Alternatively, the owner may decide to walk away and find a different laboratory that is better suited or more compliant.

- Routine audits: Dependent on the criticality of the work placed with a contract laboratory, the owner may want to carry out routine audits on a regular basis which may vary from annually to every 2–3 years. In essence, the aim of this audit is to confirm that the laboratory's quality management system operates as documented and that the analytical work carried out on behalf of the owner has been to the standards in the quality agreement, including the required records of complete data.

- For cause audits: There may be problems arising that require an audit for a specific reason, such as the failure of a number of batches or problems with a specific analysis or even suspected falsification.

Audits are a key mechanism to provide the confidence that the contact laboratory is performing to the requirements of the quality agreement or contract. If noncompliances are found, they can be resolved before any regulatory inspection.

Who Is Involved in a Quality Agreement? (Part II)

There will be a number of people within the quality function of both organizations involved in the negotiation and operation of a quality agreement. Typically, some of the roles involved could be

- Quality assurance coordinator

- Head of laboratory from the sponsor and the corresponding individual in the contract laboratory

- Senior scientists for each analytical technique from each laboratory

- Analytical scientists

- Auditor from the sponsor company for routine assessment of the contract laboratory

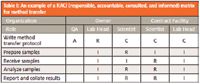

One of the ways that each role is carried out is to define them in the agreement, which can be wordy. An alternative is to use a RACI (pronounced "racy") matrix, which stands for responsible, accountable, consulted, and informed. This approach defines the activities involved in the agreement and for each role assigns the appropriate activity. For example, the release of the batch would be the responsibility of the sponsor's quality unit in the United States or the qualified person in Europe.

- Responsible: This is the person who performs a task. Responsibilities can be shared between two or more individuals.

- Accountable: This is the single person or role that is accountable for the work. Note that although responsibilities can be shared, there is only one person accountable for a task; equally so, it is possible that the same individual could be both responsible and accountable for a task.

- Consulted: These are the people asked for advice before or during a task.

- Informed: These are the people who are informed after the task is completed.

A simple RACI matrix for the transfer of an analytical procedure between laboratories is shown in Table I. The table is constructed with the tasks involved in the activity down the left hand column and the individuals involved from the two organizations in the remaining five columns. The RACI responsibilities are shared among the various people involved.

Table I: An example of a RACI (responsible, accountable, consulted, and informed) matrix for method transfer

Further Information on Quality Agreements

For those that are interested in gaining further information about quality agreements there are a number of resources available:

- The Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients Committee (APIC) offers some useful documents such as "Quality Agreement Guideline and Templates" (12) and "Guideline for Qualification and Management of Contract Quality Control Laboratories" (13) available at www.apic.org. The scope of the latter document covers the identification of potential laboratories, risk assessment, quality assessment, and on-going contract laboratory management (monitoring and evaluation). Finally, there is an auditing guidance available for download (14).

- The Bulk Pharmaceutical Task Force (BPTF) also has a quality agreement template (15) available for download from their web site.

Summary

The FDA acknowledges in the conclusions to the draft guidance (1) that written quality agreements are not explicitly required under GMP regulations. However, this does not relieve either party of their responsibilities under GMP, but a quality agreement can help both parties in the overall process of contract analysis — defining, establishing, and documenting the roles and responsibilities of all parties involved in the process. In contrast, under EU GMP quality agreements are a legal and regulatory requirement.

References

(1) FDA, "Contract Manufacturing Arrangements for Drugs: Quality Agreements," draft guidance for industry, May 2013.

(2) European Union Good Manufacturing Practices (EU GMP), Outsourced Activities, Chapter 7, effective January 31, 2013.

(3) International Conference on Harmonization, ICH Q10 Pharmaceutical Quality Systems step 4 (ICH, Geneva, Switzerland, 1997).

(4) R.D. McDowall, Spectroscopy 26(4), 24–33 (2011).

(5) European Commission Health and Consumers Directorate-General, EudraLex: The Rules Governing Medicinal Products in the European Union. Volume 4, Good Manufacturing Practice Medicinal Products for Human and Veterinary Use. Annex 11: Computerised Systems (Brussels, Belgium, 2010).

(6) FDA "GMP for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients," guidance for industry, Federal Register, (2001).

(7) European Union Good Manufacturing Practices (EU GMP) Part II - Basic Requirements for Active Substances used as Starting Materials, effective July 31, 2010.

(8) 21 CFR 211, "Current Good Manufacturing Practice for Finished Pharmaceutical Products" (2009).

(9) Marx Brothers, "A Night At The Opera," MGM Films (1935).

(10) R.D. McDowall, Spectroscopy 28(4), 18–25 (2013).

(11) W. Shakespeare, Henry V1 Part II, Act IV, Scene 2, Line 77.

(12) "Quality Agreement Guideline and Templates," Version 01, Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients Committee, December 2009, http://apic.cefic.org/publications/publications.html.

(13) "Guideline for Qualification and Management of Contract Quality Control Laboratories," Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients Committee, January 2012, http://apic.cefic.org/publications/publications.html.

(14) Audit Programme (plus procedures and guides), Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients Committee, July 2012, http://apic.cefic.org/publications/publications.html.

(15) Quality Agreement Template, Bulk Pharmaceutical Task Force, 2010, http://www.socma.com/AssociationManagement/?subSec=9&articleID=2889.

R.D. McDowall R.D. McDowall is the principal of McDowall Consulting and the director of R.D. McDowall Limited, and the editor of the "Questions of Quality" column for LCGC Europe, Spectroscopy's sister magazine. Direct correspondence to: spectroscopyedit@advanstar.com