Tutorial: Attenuation of X-Rays By Matter

Spectroscopy

In this X-ray tutorial, the authors attempt to answer the frequently asked question, "How deep do the X-rays penetrate my sample?"

X-rays are attenuated as they pass through matter. That is, the intensity of an X-ray beam decreases the farther it penetrates into matter. Basically, each interaction of an X-ray photon with an atom of the material removes an X-ray from the beam, decreasing its intensity.

The amount of decrease in intensity of the X-ray beam depends upon two factors:

- The depth of penetration (x) or thickness

- A characteristic of the material called its "absorption coefficient" (A).

The intensity decreases exponentially with the distance traveled, or

I = I0exp (– Ax)

where I0 is the initial X-ray beam intensity. Note that this exponential decay of photon intensity applies in the optical region of the electromagnetic spectrum as well. In this region, it is known as the Beer–Lambert law.

The quantity A is the linear absorption coefficient. Note that the term μ , by conventional nomeclature, is often referred to as the linear attenuation coefficient. These two coefficients are related by the density of the material (ρ) as μ = A/ρ.

Attenuation Length

An interesting application of this equation is to determine the depth of penetration of X-rays. The attenuation length is defined as the depth into the material where the intensity of the X-rays has decreased to about 37% (1/e) of the value at the surface. That is, I = (1/e)I0, or I/I0 = 1/e. [Recall that e, sometimes called Euler's number or Napier's constant, is the base of natural logarithms, or e ≈ 2.7183.] Then, substituting into Equation 1, we get

(I/I0) = exp (–μρx)

ln (1/e) = (–μρx)

–1 = (–μρx)

x = 1/(μρ)

This also is referred to as the "mean free path" of the X-rays.

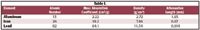

For example, given a 109Cd radioisotope source of X-rays with an energy of 22.1 keV, how far do these penetrate a piece of pure iron, (atomic number 26)? From Table I, we find the mass absorption coefficient for iron at 22.1 keV is μ = 18.2 cm2/g. The density of iron ρ = 7.86 g/cm3. Plugging in the numbers, we find x = 0.007 cm = 0.07 mm = 70 μm. A comparison of this depth for the same incoming X-ray energy both for lighter and heavier elements is shown in Table I.

Table 1

Measuring the Mass Absorption Coefficient

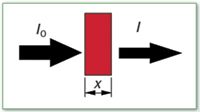

Figure 1: Attenuation of X-ray intensity.

We need a source of X-rays — the radioisotope Cd-109 or an X-ray tube, for example — and a detector such as a Geiger counter. Place a piece of foil of thickness t1 between the source and detector and measure the radiation intensity I1, as shown in Figure 1. Now place a second piece of foil with a thickness t2 in the path and measure the new intensity I2. If the original beam intensity is I0, then we can write

I1 = I0 exp (–μρt1)

I2 = I0 exp (–μρt2)

Dividing these equations,

(I1/I2) = exp (– μρt1)/exp (– μρt2)

or

μ = ln (I1/I2)/ρ (t2 – t1)

For example, we use an X-ray tube run at 35 kV and a 0.025-mm thick piece of copper foil. With one foil thickness, our Geiger counter measures 185,000 counts per minute (cpm). When the foil is doubled and the measurement repeated, we find a count rate of about 155,000 cpm. The density of copper is 8.94 g/cm3. Then

μ = ln (185,000/155,000) / (8.94 g/cm3)(0.005 cm – 0.0025 cm)

or

μ = 7.9 cm2/g

The accepted value for the mass absorption coefficient of copper at this energy is approximately 7.0 cm2/g. This is a reasonable agreement given the rather crude experimental set-up in which the Geiger counter used had a low-resolution analog readout meter.

Multicomponent Systems

When a sample contains more than one component, the total mass absorption coefficient is the sum of the individual coefficients, each multiplied by the weight fraction present. That is,

Consider an alloy containing 70% Ni and 30% Mo. What is the mass absorption coefficient of this sample at an excitation energy of 22.1 keV (109Cd radioisotope emission)?

For nickel: μ (22.1 keV) = 23.8 cm2/g

For molybdenum: μ (22.1 keV) = 61.9 cm2/g

Therefore,

μs = (CNi)(μNi) + (CMo)(μMo) = (0.7)(23.8) + (0.3)(61.9) = 35.3 cm2/g

Absorption "Edges"

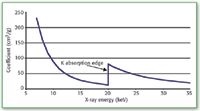

The mass absorption coefficient of a material is energy dependent. In general, this coefficient decreases with increasing energy of the penetrating X-rays. Figure 2 shows a plot of the mass absorption coefficient for molybdenum from about 7 to 35 keV.

Figure 2: Mass absorption coefficient of molybdenum.

Note, however, that we do observe sharp increases in this coefficient at certain energies. These discontinuities occur at the minimum energies for excitation of a particular electron shell, that is, at the binding energies. For example, in Figure 2, we find a discontinuity at about 20 keV. This is the K-shell electron binding energy.

These discontinuities in the mass absorption coefficient are called "absorption edges." After an absorption edge, the general decrease with increasing energy continues.

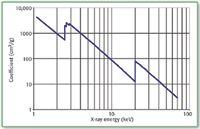

Figure 3 presents the energy dependence of the mass absorption coefficient of Molybdenum in the more traditional log–log format. Also evident are the L absorption edges at about 2.5, 2.6, and 2.9 keV. These correspond to the electron binding energies of the three L-shell subshells.

Figure 3: LogâÂÂlog plot of mass absorption coefficient of molybdenum.

Conclusion

The attenuation of X-rays by matter is a specific example of the more general phenomenon of the attenuation of electromagnetic radiation by matter. In the optical region of the E–M spectrum, this phenomenon finds significant spectrometric application in the form of the Beer–Lambert law.

In the X-ray region, this attenuation is characterized by the mass absorption coefficient of the matter, an important consideration in X-ray fluorescence spectrometry. A frequently asked question is, "How deep do the X-rays penetrate my sample?" We have attempted to answer this question here.

Appendix: Derivation of the Beer–Lambert Law

1. The number of photons absorbed ΔI in a given thickness Δx is proportional to the incident intensity I and the thickness:

ΔI proportional to IΔx

where the minus sign indicates a decreasing intensity with thickness.

2. Let A be the constant of proportionality, the absorption coefficient, and we can write

ΔI = AIΔx

3. Letting the deltas become infinitesimally small, we have, in differential notation,

dI = AIdx

4. Integrating from x = 0 to a depth x, we get

I = I0 exp (–Ax)

where I0 is the initial intensity at x = 0.

Notes

1. For mass absorption coefficients and other X-ray related element properties, see www.csrri.iit.edu/periodic-table.html.

2. For a free copy of the X-Ray Data Booklet from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA, go to http://xdb.lbl.gov.

Volker Thomsen, Debbie Schatzlein, and David Mercuro are with Thermo Electron Corporation's Portable Elemental Analysis Division, formerly known as NITON LLC (Billerica, MA). E-mail: VThomsen@NITON.comDSchatzlein@NITON.com and DMercuro@NITON.com

High-Speed Laser MS for Precise, Prep-Free Environmental Particle Tracking

April 21st 2025Scientists at Oak Ridge National Laboratory have demonstrated that a fast, laser-based mass spectrometry method—LA-ICP-TOF-MS—can accurately detect and identify airborne environmental particles, including toxic metal particles like ruthenium, without the need for complex sample preparation. The work offers a breakthrough in rapid, high-resolution analysis of environmental pollutants.

Advancing Corrosion Resistance in Additively Manufactured Titanium Alloys Through Heat Treatment

April 7th 2025Researchers have demonstrated that heat treatment significantly enhances the corrosion resistance of additively manufactured TC4 titanium alloy by transforming its microstructure, offering valuable insights for aerospace applications.