Is Traceability the Glue for ALCOA, ALCOA+, or ALCOA++?

Confused from Quality Control (QC) writes, “Doctor, Doctor, give me the news! Originally, it was just ALCOA criteria for data integrity, then a plus was added, but now its ALCOA++. What should I do? Help me please!”

Well, Confused, the good news is that the doctor is in and can help you unravel the delights and joys of ALCOA and its two offspring. We will trace the terminology from its inception in the last century and follow its evolution through two iterations from the original five criteria to 10 with ALCOA++.

What do you mean you have never heard of ALCOA++? Tut, tut, you are not keeping up with your regular medication of regulatory guidance documents. You really must do better. As punishment write out 100 times, I must not use spreadsheets for GXP calculations (1,2).

To manage the expectations of readers, the use of ALCOA in this column does not refer to the Aluminium Company of America. I realize the disappointment that this may cause to many but sometimes, as you probably know, life stinks.

How Can You Determine the Integrity of Data?

A problem in the current regulatory climate is how to determine the integrity of the data in a record. This issue is not only prominent in regulated laboratories, but in all laboratories because any decision made using analytical data needs the integrity to be assured (can you trust the data?) before a decision is made using the extracted information. What is needed is a set of criteria that can be applied to the records set to provide assurance that the integrity of the data is good. Enter the ALCOA criteria, which are the focus of this column.

In The Beginning....

The ALCOA story goes back to last century: Stan Wollen, who was an FDA Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) inspector, was involved in training fellow inspectors on new inspection techniques. He developed the acronym as a means of understanding and evaluating GLP study data for data quality and not data integrity. As aluminium kitchen foil made by the ALCOA company was widely available, he used ALCOA as the basis for the following five criteria that could be applied to any data set:

- Attributable

- Legible

- Contemporaneous

- Original

- Accurate.

These criteria are outlined in a publication entitled, Data Quality and the Origin of ALCOA, and available for download online (3). Wollen makes the point that the individual elements of ALCOA were already present in existing Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) and GLP regulations. What he did was organize them into an easily memorized acronym (4).

Plagiarism Is the Sincerest Form of Flattery

Fast forward to this century, and we find that Wollen’s ALCOA data quality criteria have been taken by various regulatory guidance documents and repurposed for use as a cornerstone of data integrity in regulatory guidance documents from the following agencies:

- Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) 2015 and 2018 (5,6)

- World Health Organization (WHO), 2016 (7)

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA), 2018 (8).

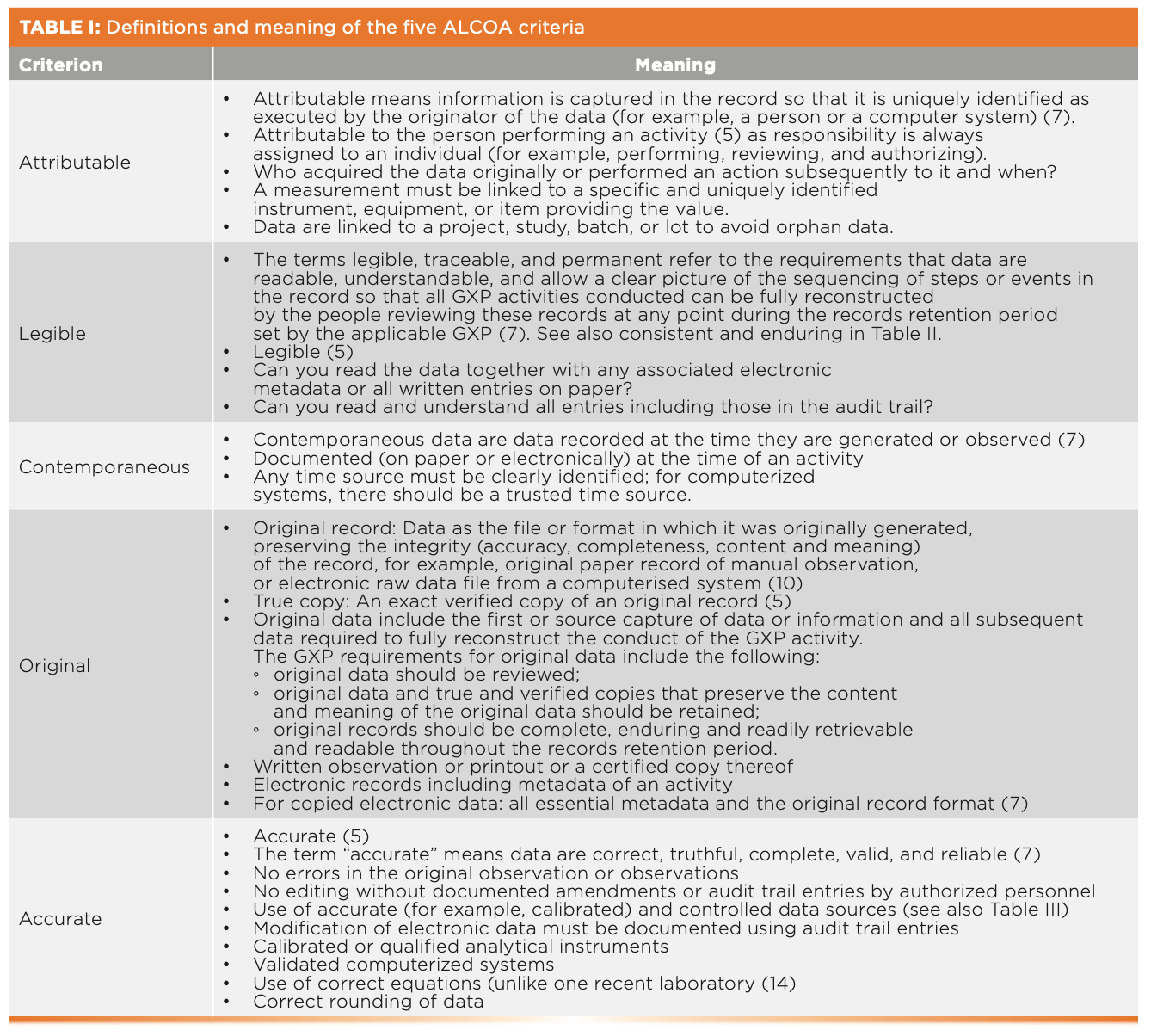

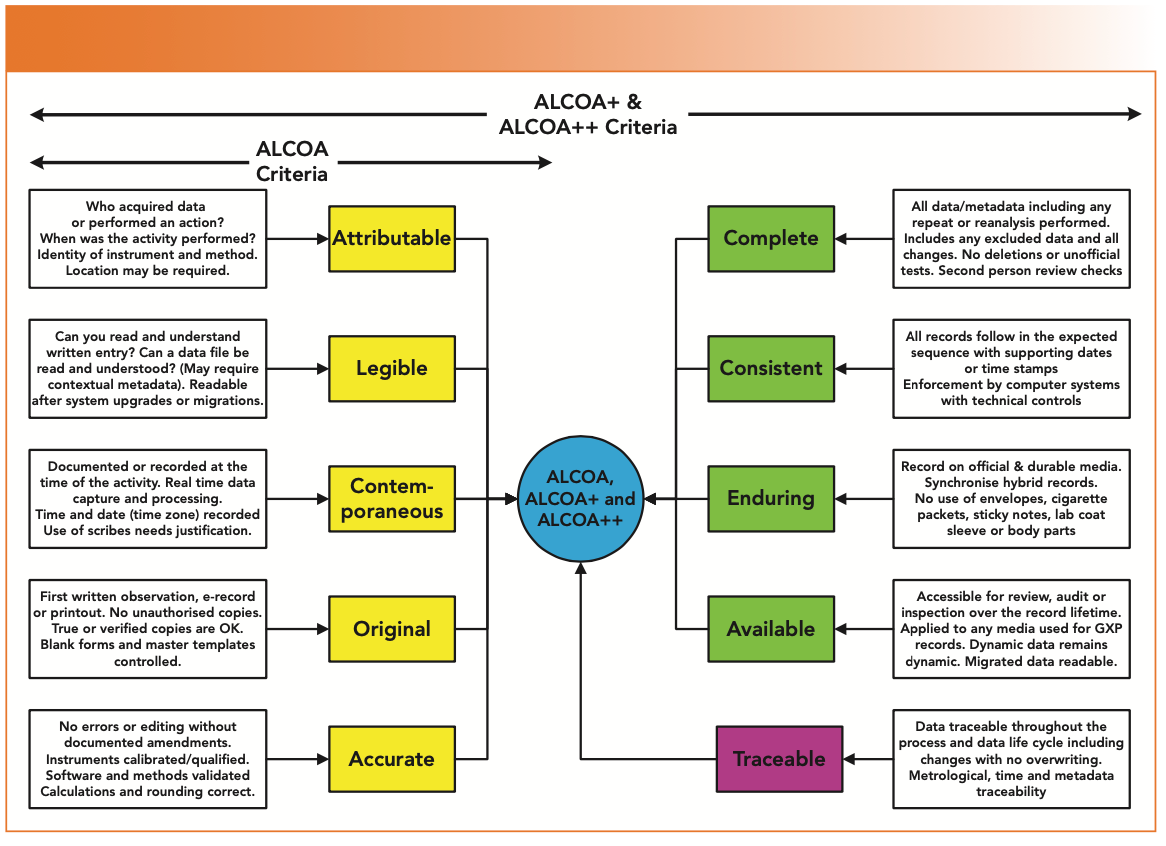

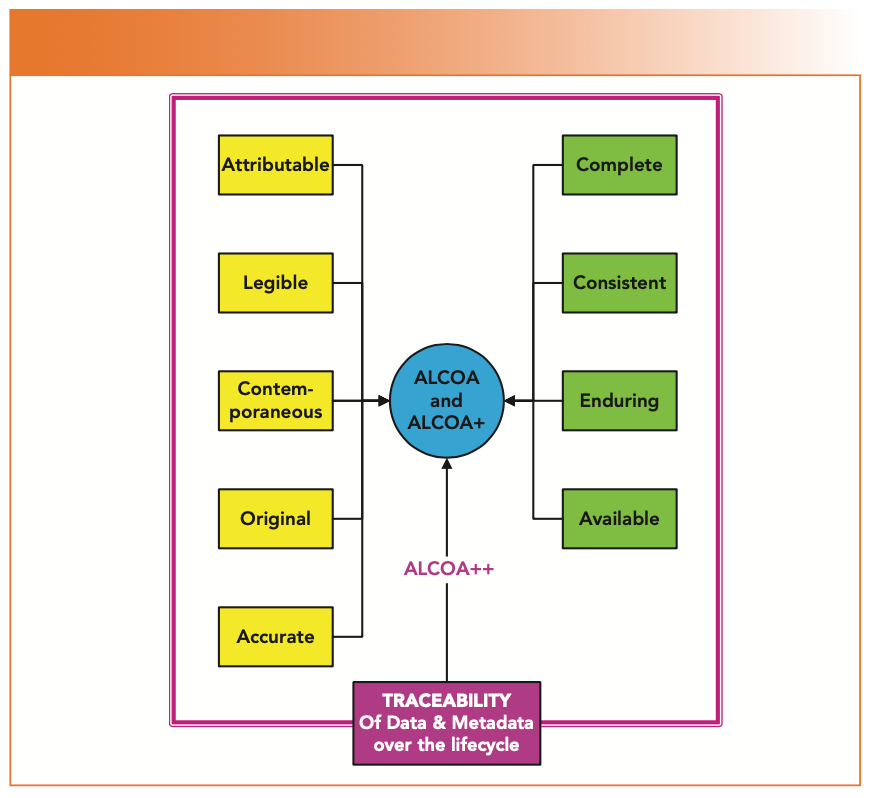

The data integrity definitions of the five ALCOA criteria are presented with some explanation in Table I and are shown in yellow in Figure 1. Please read both; they are free of charge. Note that the WHO guidance document includes both permanent and understandable under “legible” (7). This WHO guidance has the best discussion of ALCOA criteria in Appendix 1 (7), and it is essential reading for anyone involved with data integrity.

FIGURE 1: ALCOA, ALCOA+, and ALCOA++ criteria collated from regulatory guidance documents.

Unfortunately, the WHO 2016 guidance has been superseded by an inferior guideline in 2021 (9) of limited scope that has deleted the superb ALCOA appendix. This new guidance still uses ALCOA with the addition of “enduring,” which is shown later in Table IV. My advice is to ignore the new guidance and stay with the 2016 document (7).

The 2018 MHRA data integrity guidance mentions in section 3.10:

.... ALCOA was historically regarded as defining the attributes of data quality that are suitable for regulatory purposes. .... (6).

The origin of ALCOA was focused on data quality, but the same criteria can be applied to data integrity, given that the same data set is involved. Therefore, ALCOA attributes apply to both data quality and data integrity. The two terms were discussed in an earlier “Focus on Quality” column (11).

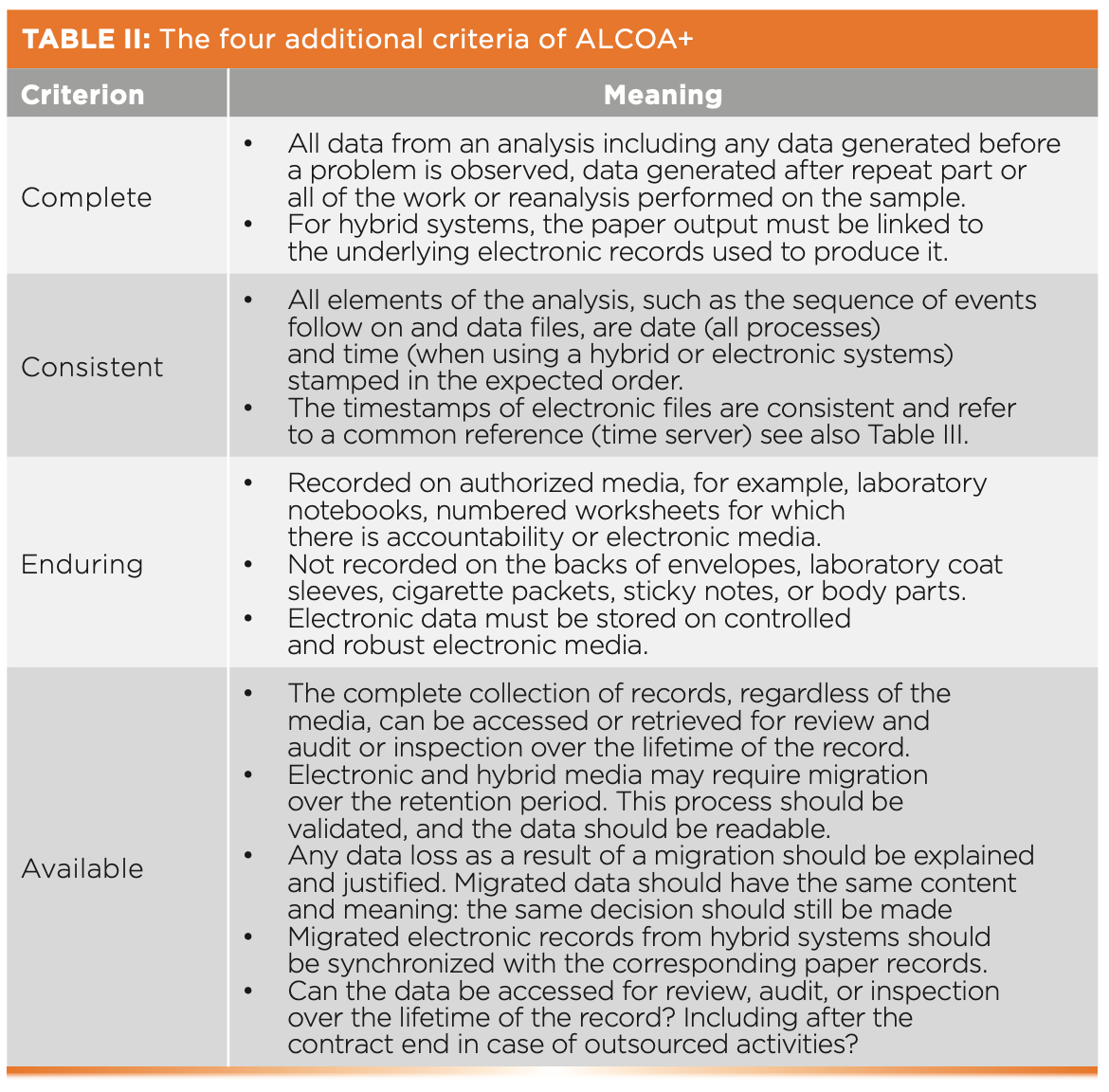

Add Four Criteria to make ALCOA+

In 2010, the European Medicines Agency issued a guidance on electronic source data in clinical trials (12), where four additional criteria were added to make ALCOA+. These four criteria were:

- Complete

- Consistent

- Enduring

- Available.

The definitions are presented with some explanation in Table II and are shown in green in Figure 1. The 2021 Pharmaceutical Inspection Convention/Pharmaceutical Inspection Cooperation Scheme (PIC/S) data integrity guidance also uses the ALCOA+ criteria (13).

Official media must be used to record data to ensure that they are “enduring” (equivalent to “permanent” in the WHO guidance mentioned earlier). However, Table II and Figure 1 list some unacceptable and unofficial media including a laboratory coat sleeve or the occasional body part—just don’t even think about these alternatives. You don’t want to have a starring role in a regulatory citation like the individual who wrote GMP information on his hand in front of an inspector (14).

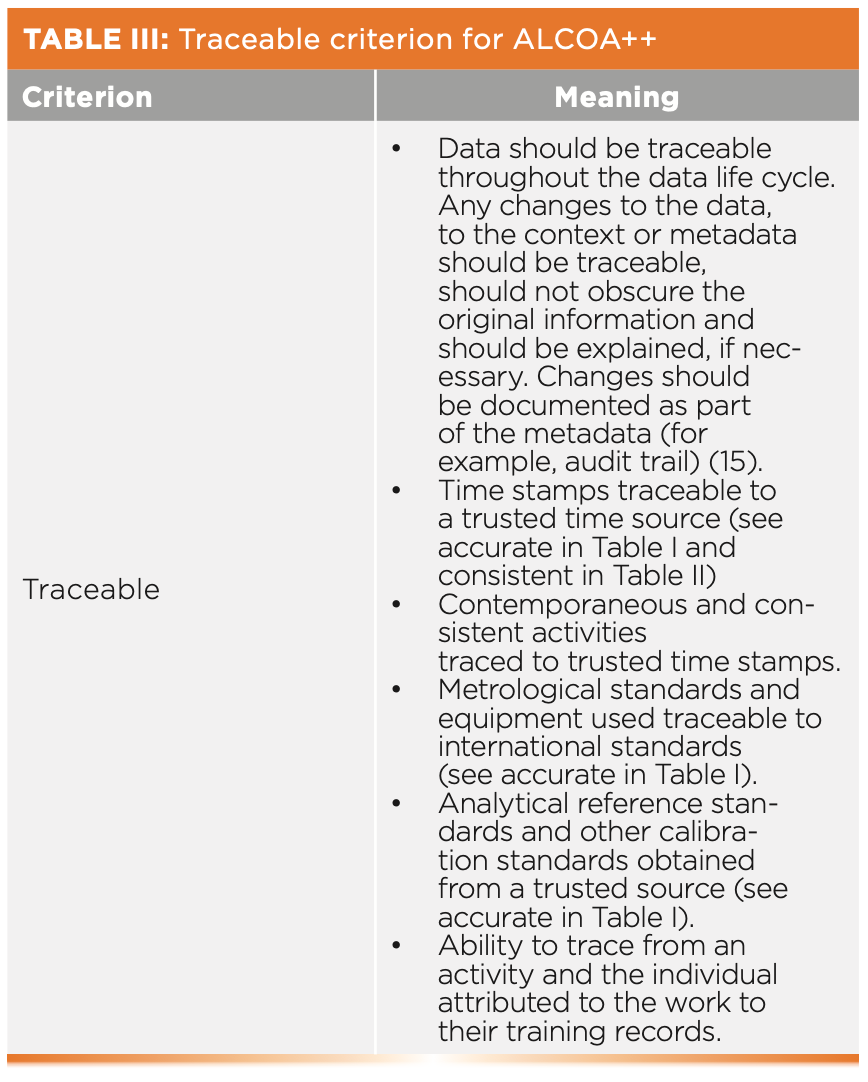

Adding Up Nicely the Tenth ALCOA++ Criterion

The tenth and latest ALCOA criterion is “traceable,” from a draft EMA guidance on computerized systems and electronic data in clinical trials (15). The definition and meaning are presented in Table III and shown in purple in Figure 1.

There is a debate about whether a new criterion is necessary. You will notice in Tables I and II that there are references to Table III, which means that traceability is implied in the existing ALCOA+ criteria.

However, from an inspector’s or auditor’s perspective, any process or system should be able to show what has happened from data acquisition to generation of the reportable result. I also want to be able to do the same in reverse, from the result to the acquisition. Ideally, any system or process should facilitate this easily and be self-evident, including documenting any problems that occurred and their resolution.

Many would argue that the criterion “traceable” is implicit in ALCOA and ALCOA+. However, the implication of the term is the problem; it is always better in data regulatory guidance to be explicit. For example, consider the definition of raw data in the United States and Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) GLP (4,16). There is the need to be able to reconstruct the study report from the original observations and activities, which is an explicit requirement for traceability. My argument is that if something is implied, then it may not be recognized as a necessity and not acted upon.

The next question is whether we need to change the name of ALCOA+ to ALCOA++. From a personal perspective, ALCOA++ is unwieldy and 10 ALCOA+ terms would be acceptable for me. However, others are just as content to leave ALCOA+ as nine terms with traceability implied. From the cross references between the three tables in the column, you can see that traceability is implicit already in ALCOA+.

Is Traceability the Glue for ALCOA+?

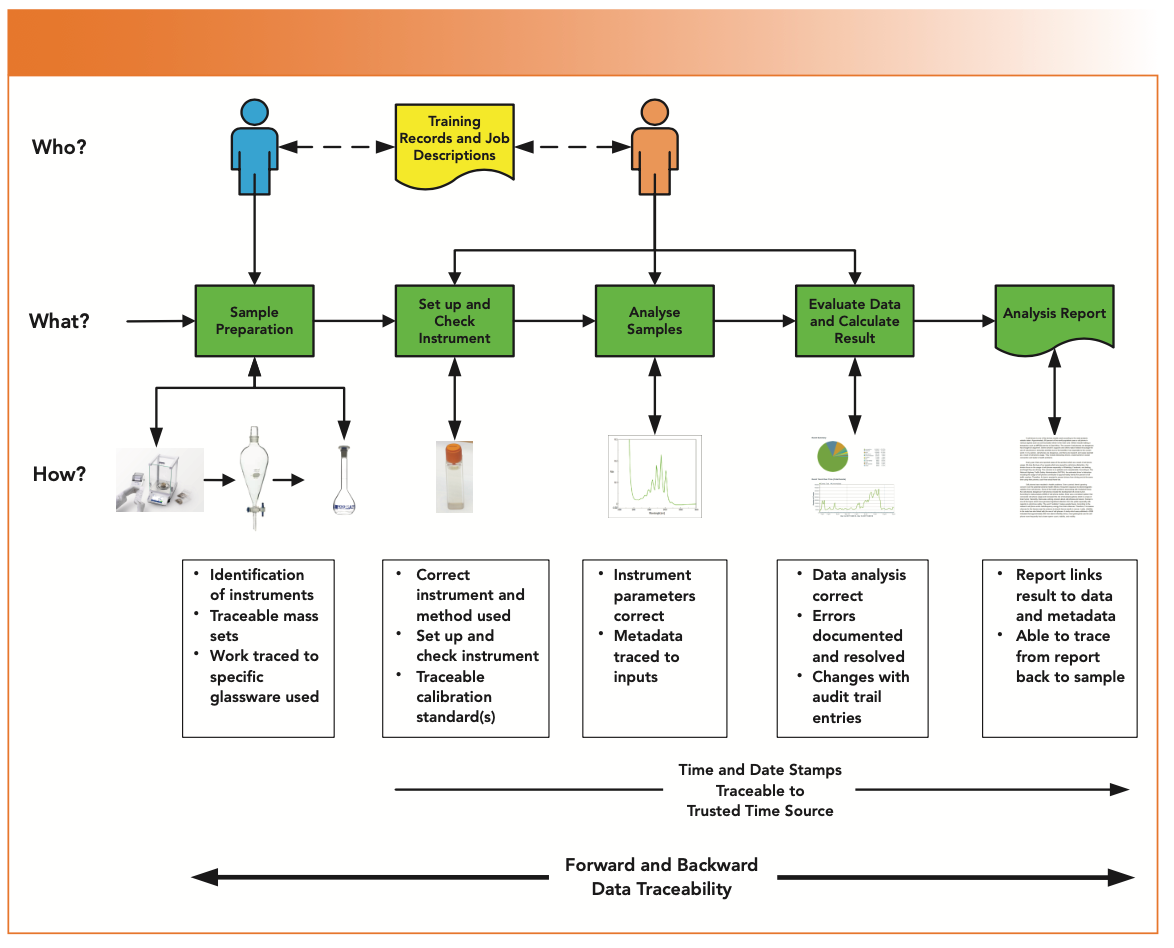

However, there is more to traceability and we need to explore the full impact of this criterion because it is essential for the interactions between the other ALCOA criteria as presented in Figure 3. Each ALCOA criterion does not exist on its own in a silo but interacts with other criteria.

- The center of Figure 3 depicts an analytical process in green from sample preparation to the analysis report and represents the “what” of what must be done.

- At the top, two analysts performed the work and are the “who”: there is one analyst for the sample preparation and a second analyst for the analysis. Note that no second person review is shown. A common audit technique is to select an individual who performed a task and trace back to his or her training records and job description to ensure that the person had the combination of education, training, and experience to do the work at the time it was done.

- The process flow shows the individual tasks that represent the “how,” and display how the analytical procedure is performed and the end result that is achieved. Traceability runs throughout the entire process to ensure that you have used the right instrument, glassware, instrument method, operating parameters, and so forth.

- Data entered into a computerized system (batch and sample number, weights, and so on) must be traceable to the external source records outside of it.

- Any changes to the data or metadata must have corresponding audit trail entries that trace the changes and the reasons for them.

- The use of calibrated mass sets,reference standards, and calibration standards all require further traceability to calibration certificates or certificates of analysis.

- Glassware needs to be identified and recorded in case of investigations. Recently, quick response (QR)–coded volumetric glassware has been introduced so that each flask or pipette is uniquely identified; this information can be set up in an informatics application. When any glassware is used, the code is scanned so that any items used are recorded automatically. However, in any automated process, there must be the ability to allow an analyst to record any issues in free text if a problem is found, which is important in complying with the “Analyst Responsibilities in the FDA Out of Specification” guidance (17) in case an activity has to be repeated because of a mistake.

- To ensure reliable time and date stamps, a computerized system should be linked to the network with a time server that is synchronized to an external trusted time source, such as a network time protocol (NTP) server or a national legal time source.

FIGURE 3: A spectroscopic analysis illustrating the role of traceability in en- suring data integrity.

Traceability ensures trusted and reliable records and activities that in turn ensure integrity of data and the whole record set. Therefore, you can see why traceability, an implied requirement of ALCOA and ALCOA+, is an important addition.

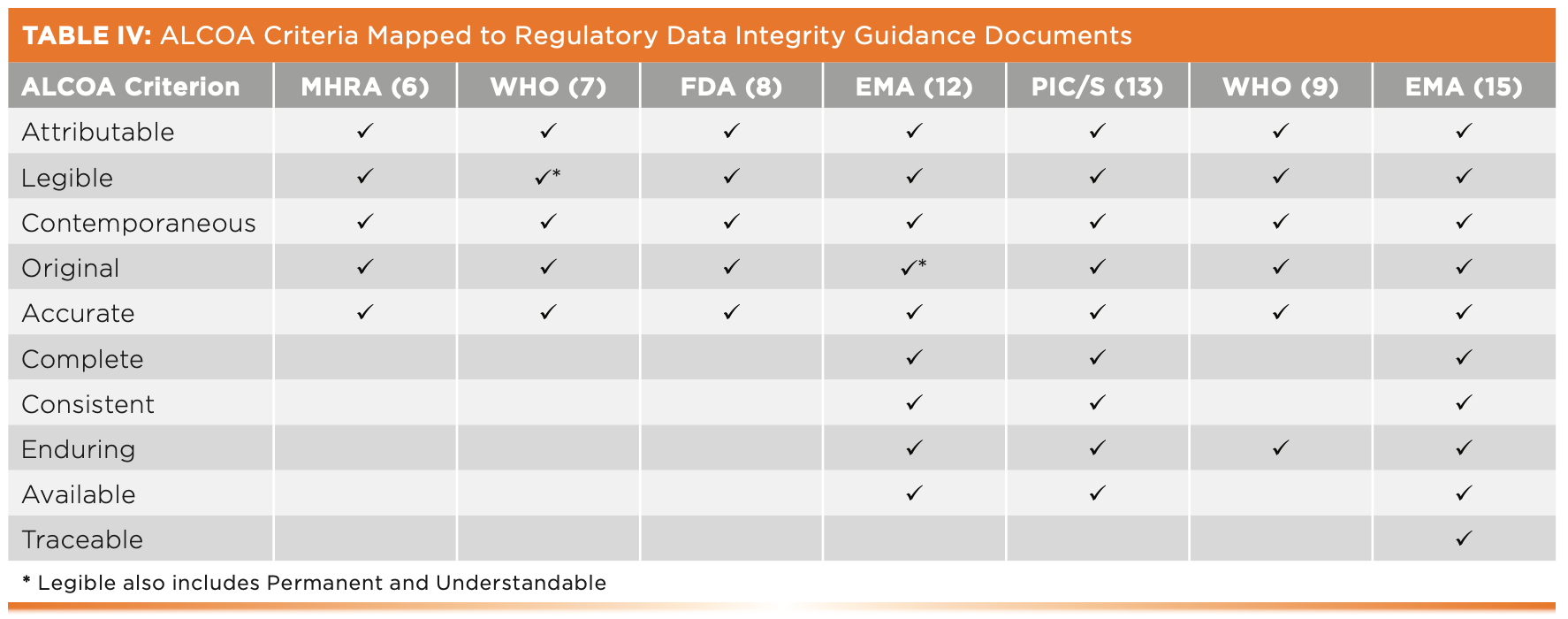

Mapping all ALCOA Criteria Across Regulatory Guidance Documents

To complete our discussion, Table IV maps all 10 ALCOA criteria to the respective GMP regulatory guidance documents for data integrity available at the start of 2022. As can be seen, the PIC/S (13) and two EMA GCP guidance documents (12,15) are the guidances with ALCOA+ and ALCOA++ criteria. However, reiterating my advice earlier, Appendix 1 of the WHO guidance (7) is still the must-read section to have an in-depth understanding of ALCOA, supplemented with PIC/S PI-041 (13) and the latest EMA (15) guidances for ALCOA+ and ALCOA++ criteria, respectively.

Summary

The criteria for data integrity continue to evolve, and the proposed criterion of traceability appears to be the dark matter that holds the remaining ALCOA+ criteria together. However, it is traceability that shows that each ALCOA criterion does not exist in a silo, but that they all interact with and are dependent upon each other.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Ulrich Köllisch and Chris Burgess for their input into the review of Figure 1. Figure 2 and the encompassing role of traceability in ensuring data integrity were developed during discussions with Chris Burgess. I would also like to thank Yves Samson, Peter Baker, and Chris Burgess for providing excellent review comments during the preparation of this paper.

FIGURE 2: Impact of traceability on the ALCOA+ criteria (with acknowledgement to Chris Burgess).

References

(1) R.D. McDowall, LCGC Europe 33(9), 468–476 (2020).

(2) R.D. McDowall, Spectroscopy 35(9), 27–31 (2020).

(3) S.W. Wollen, Data Quality and the Origin of ALCOA in The Compass Summer 2010, Newsletter of the Southern Regional Chapter, Society of Quality Assurance (2010). Available from: http://www.southernsqa.org/newsletters/Summer10.DataQuality.pdf

(4) 21 CFR 58 Good Laboratory Practice for Non-Clinical Laboratory Studies (Food and Drug Administration: Washington, DC, 1978).

(5) MHRA, GMP Data Integrity Definitions and Guidance for Industry 2nd Edition (Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency: London, United Kingdom, 2015).

(6) MHRA, GXP Data Integrity Guidance and Definitions (Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, London, United Kingdom, 2018).

(7) World Health Organization, Technical Report Series No. 996 Annex 5 Guidance on Good Data and Records Management Practices (WHO, Geneva, Switzerland, 2016).

(8) FDA Guidance for Industry Data Integrity and Compliance With Drug CGMP Questions and Answers (Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, 2018).

(9) WHO, Technical Report Series 1033, Annex 4 Guideline on Data Integrity (World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 2021).

(10) WHO Handbook, Good Laboratory Practices (GLP) Quality Practices for Regulated Non Clinical Research and Development, Second Edition (World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 2009).

(11) R.D. McDowall, Spectroscopy 30(11), 22–28 (2019).

(12) European Medicines Agency, Reflection paper on expectations for electronic source data and data transcribed to electronic data collection tools in clinical trials (European Medicines Agency, London, United Kingdom, 2010).

(13) PIC/S PI-041, Good Practices for Data Management and Integrity in Regulated GMP/GDP Environments Draft (Pharmaceutical Inspection Convention/Pharmaceutical Inspection Cooperation Scheme, Geneva, Switzerland, 2021).

(14) FDA 483 Observations Aurobindo Pharma Ltd. (FDA, Rockville, MD, 2021).

(15) EMA Draft Guideline on Computerized Systems and Electronic Data in Clinical Trials (European Medicines Agency, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021).

(16) OECD Series on Principles of Good Laboratory Practice and Compliance Monitoring Number 1, OECD Principles on Good Laboratory Practice (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Paris, France, 1998).

(17) FDA Guidance for Industry Out of Specification Results (FDA, Rockville, MD, 2006).

R.D. McDowall is the director of R.D. McDowall Limited and the editor of the “Questions of Quality” column for LCGC Europe, Spectroscopy’s sister magazine. Direct correspondence to: SpectroscopyEdit@MMHGroup.com ●

Measuring Soil Potassium with Near-Infrared Spectroscopy

January 8th 2025Researchers have developed a novel three-step hybrid variable selection strategy, SiPLS-RF(VIM)-IMIV, to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of soil potassium measurement using near-infrared spectroscopy, offering significant advancements for precision agriculture and real-time soil monitoring.