New Study Highlights Abnormal Connectivity in Prefrontal Cortex of MCI Patients

A recent study published in Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience by Wenyu Jiang and colleagues in China found that patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) exhibit abnormal functional connectivity in the right prefrontal cortex as revealed by fNIRS, highlighting potential cognitive implications and the protective role of education.

A recent study published in Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience has revealed new information about the brain's functional connectivity (FC) patterns in individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) (1).

MCI is often an early indicator of early onset Alzheimer’s disease. Although symptoms of MCI are similar to those with dementia or Alzheimer’s disease, it is considered an intermediate stage, meaning that it is a condition in which people experience more memory issues compared to others in their age group (1,2). Approximately 10–20% of people over 65 have MCI (2). Several factors contribute to people contracting this condition. People who are diabetic have an increased risk, and genetics also play a critical role in determining the probability of someone contracting MCI (2).

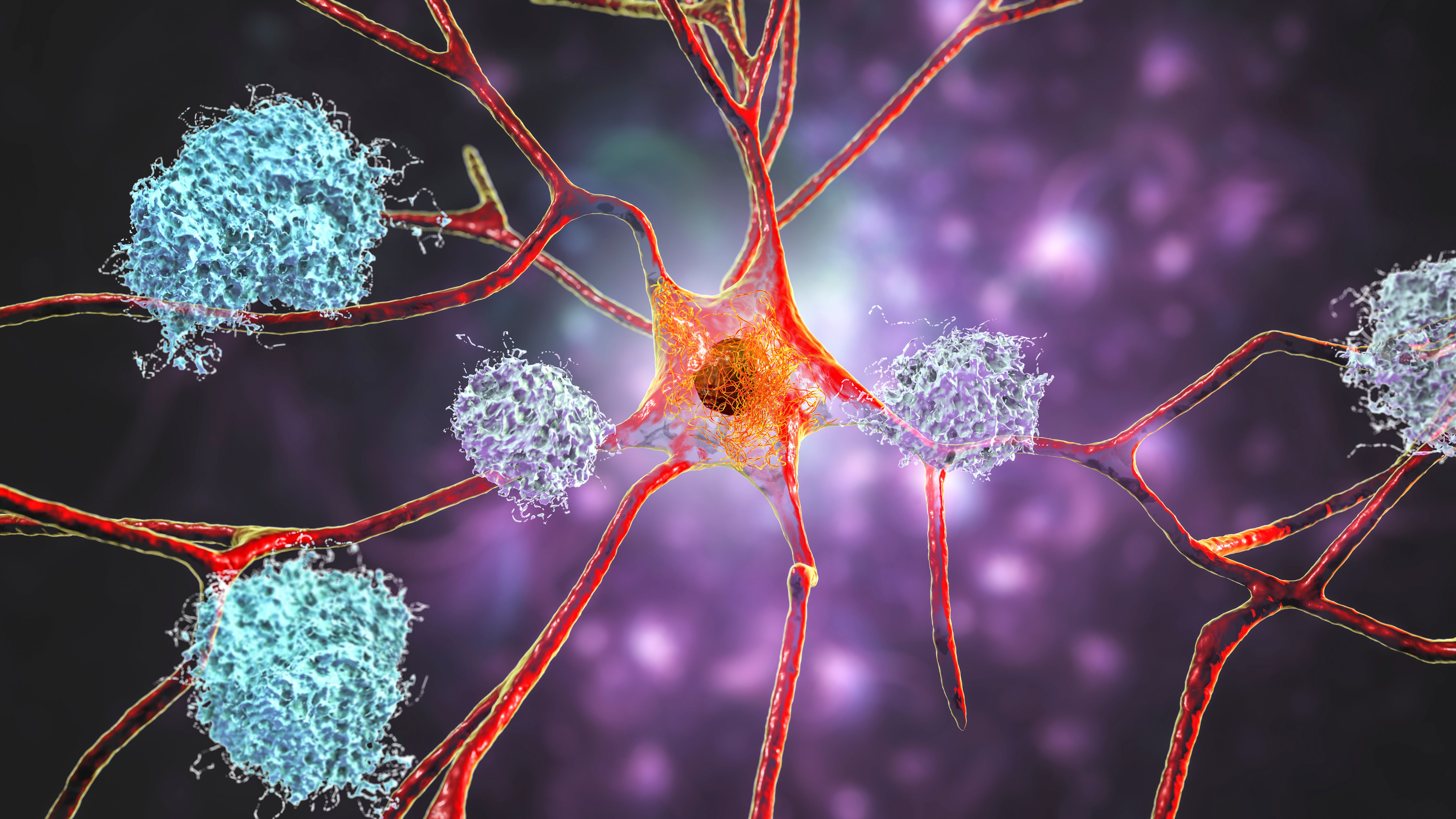

Neurons in Alzheimer's disease. Illustration showing amyloid plaques in brain tissue | Image Credit: © Dr_Microbe - stock.adobe.com

In their study, Wenyu Jiang of the Department of Neurological Rehabilitation of Jiangbin Hospital of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region and his team focused on how functional brain connectivity in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) differs in MCI patients compared to healthy individuals and what implications these differences might have on cognitive function (1).

The study involved a cohort of 67 patients diagnosed with MCI and a control group of 71 healthy individuals. All participants underwent cognitive assessments using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) to analyze brain activity and connectivity patterns (1). The MoCA is one of the most popular tests to evaluate one’s cognitive ability. It has been routinely used in clinical analysis since 2000 (3).

Using this test, the researchers determined that patients with MCI exhibited significantly lower MoCA scores compared to the healthy control group (p < 0.001), confirming their cognitive impairment (1). The researchers also noted an enhanced subnetwork of connectivity within the right prefrontal cortex of the MCI group. This subnetwork comprised four critical pairs of channel connections: CH12-CH15, CH12-CH16, CH13-CH15, and CH13-CH16 (1).

The researchers found in their study that there is a connection between these channel pairs' FC values and cognitive function. The study discovered that both the FC values within this subnetwork and the education duration of the participants were positively correlated with their MoCA scores (1). What this means is that individuals with higher FC values performed better on cognitive tests compared to those with lower FC values (1).

As part of their study, the researchers created a linear regression model to explain the relationship between the FC values, education duration, and the MoCA scores. For their model, the FC values and education duration served as the y (dependent variables), and the MoCA values represented the x (independent variable) (1). The model demonstrated a notable explanatory power, accounting for 25.7% of the variance in cognitive function (adjusted R2 = 0.257, F = 24.723, p < 0.001) (1). This finding underscores the potential role of the PFC's functional connectivity in understanding cognitive decline in MCI, and it suggests that education may act as a protective factor against cognitive deterioration (1).

Several limitations need to be mentioned in their study, which the authors described in their paper. To start, the researchers caution that their participants came from a specific region. As a result, this limits the generalizability of the findings to broader MCI populations (1). Second, the researchers were constrained from observing long-term changes or progression from MCI to Alzheimer’s disease (1).

And finally, fNIRS, while being non-invasive and fairly accessible, does suffer from limited spatial resolution and less-than-ideal penetration depth (1). As a result, this means its drawbacks could prevent it from capturing deeper brain structures (1). Although they did not do this in their own study, the researchers suggested that future studies that implement imaging techniques like functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) for better spatial resolution or electroencephalography (EEG) for superior temporal resolution can mitigate these concerns (1).

Moreover, the study’s primary focus on the PFC might have missed critical information from other brain regions that play a role in MCI. Given that MCI involves complex, widespread changes throughout the brain, future research should adopt a more holistic approach by including multiple regions for analysis to develop a comprehensive understanding of MCI’s pathophysiology.

References

- Wu, P.; Lv, Z.; Bi, Y.; et al. Network-based Statistics Reveals an Enhanced Subnetwork in Prefrontal Cortex in Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Functional Near-infrared Spectroscopy Study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2024, 16, 1416816. DOI: 10.3389/fnagi.2024.1416816

- National Institutes of Health, What Is Mild Cognitive Impairment? Alzheimers.gov. Available at: https://www.alzheimers.gov/alzheimers-dementias/mild-cognitive-impairment (accessed 2024-11-05).

- MoCA Cognition, Home Page. MoCA Cognition. Available at: https://mocacognition.com/#:~:text=MoCA%20(Montreal%20Cognitive%20Assessment%20or,to%2018%25%20for%20the%20MMSE. (accessed 2024-11-05).

NIR Spectroscopy Explored as Sustainable Approach to Detecting Bovine Mastitis

April 23rd 2025A new study published in Applied Food Research demonstrates that near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) can effectively detect subclinical bovine mastitis in milk, offering a fast, non-invasive method to guide targeted antibiotic treatment and support sustainable dairy practices.

New AI Strategy for Mycotoxin Detection in Cereal Grains

April 21st 2025Researchers from Jiangsu University and Zhejiang University of Water Resources and Electric Power have developed a transfer learning approach that significantly enhances the accuracy and adaptability of NIR spectroscopy models for detecting mycotoxins in cereals.

Karl Norris: A Pioneer in Optical Measurements and Near-Infrared Spectroscopy, Part II

April 21st 2025In this two-part "Icons of Spectroscopy" column, executive editor Jerome Workman Jr. details how Karl H. Norris has impacted the analysis of food, agricultural products, and pharmaceuticals over six decades. His pioneering work in optical analysis methods including his development and refinement of near-infrared spectroscopy, has transformed analysis technology. In this Part II article of a two-part series, we summarize Norris’ foundational publications in NIR, his patents, achievements, and legacy.