Simple Method for Monitoring Protein Secondary Structure During Thermal Unfolding and Aggregation

Application Notebook

As the temperature increases, significant changes in the myoglobin secondary structure are observed. Between 25 °C and 70 °C, the 1649 cm-1 peak height decreases and linewidth increases. These changes in the amide I band reflect increased protein structural disorder. A temperature increase from 70 °C to 75 °C causes a drop in the 1649 cm-1 band intensity. Simultaneously, two peaks grow in at 1683 and 1637 cm-1. These changes indicate conversion of random coil/α-helix to intermolecular β-sheet. Further conversion to β-sheet is observed as the temperature rises to 90 °C. The final β-sheet structure is an insoluble aggregate. This aggregation process is not reversed when the temperature is driven back to 25 °C.

Protein secondary structure during thermal unfolding and aggregation is readily acquired using IR spectroscopy and a temperature-controlled mid-IR transmission accessory. Myoglobin was used as a model system to illustrate the method.

FT-IR spectroscopy is a powerful tool for measuring protein secondary structure. Using a temperature-controlled transmission accessory, the evolution of protein secondary structure through thermal transitions is readily accessible. In fact, the experiment and analysis are relatively quick; therefore, a set of proteins can be rapidly screened for stability and temperature-dependent conformational changes. This information is particularly important when evaluating multiple protein mutants.

Experimental

To demonstrate the simplicity of secondary structure evaluation using FT-IR spectroscopy, the well-characterized protein, myoglobin (1), was unfolded in D2O (3.5 µM, 50 µm pathlength) from 25 °C to 90 °C in 5 °C increments using the Falcon Mid-IR Transmission Accessory from PIKE Technologies, Inc. The accessory's Peltier elements allow for quick ramp rates and temperatures ranging from 5 °C to 130 °C. Temperature profile and spectral data collection was executed by PIKE TempPRO™ software. The amide I band was deconvolved by Fourier deconvolution (bandwidth 50 cm-1, enhancement 2) and frequencies were obtained from second derivative spectra.

Results

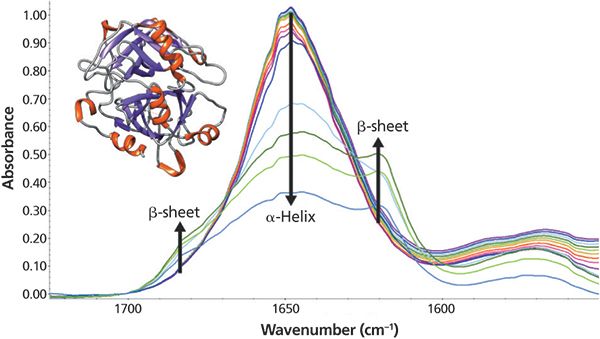

Four peaks dominate the 25 °C spectrum. The largest peak at 1649 cm-1 is assigned to α-helix and random coil structure. From the structure obtained by X-ray diffraction (Figure 1 inset), myoglobin is comprised of several α-helix and random coil regions (2). Two other peaks are observed at 1630 and 1679 cm-1 and correspond to extended chain and turn regions, respectively (1). The last peak at 1612 cm-1 is not amide I vibration but instead tyrosine side chain absorption (3). Thus, from quick spectral manipulation and inspection, the secondary structure at 25 °C is readily determined.

Figure 1: FT-IR spectra of myoglobin between 25 °C and 90 °C. Myoglobin is rendered with UCSF Chimera (4).

As the temperature increases, significant changes in the myoglobin secondary structure are observed. Between 25 °C and 70 °C, the 1649 cm-1 peak height decreases and linewidth increases. These changes in the amide I band reflect increased protein structural disorder. A temperature increase from 70 °C to 75 °C causes a drop in the 1649 cm-1 band intensity. Simultaneously, two peaks grow in at 1683 and 1637 cm-1. These changes indicate conversion of random coil/α-helix to intermolecular β-sheet. Further conversion to β-sheet is observed as the temperature rises to 90 °C. The final β-sheet structure is an insoluble aggregate. This aggregation process is not reversed when the temperature is driven back to 25 °C.

Conclusion

Using the PIKE Falcon accessory makes monitoring the thermal conversion of myoglobin from α-helix to random coil to β-sheet simple.

References

(1) F. Meersman, L. Smeller, and K. Heremans, Biophys. J. 82, 2635 (2002).

(2) S.V. Evans and G.D. Brayer, J. Mol. Biol. 213, 885 (1990).

(3) A. Barth, Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 1767, 1073 (2007).

(4) E.F. Pettersen et al., J Comput Chem 25, 1605 (2004).

PIKE Technologies, Inc.

6125 Cottonwood Drive, Madison, WI 53719

tel. (608) 274-2721

Website: www.piketech.com