Simultaneous Determination of Inorganic Forms of Arsenic, Antimony, and Thallium by HPLC–ICP–MS

Spectroscopy

A simple and rapid method for the simultaneous separation and determination of the inorganic ionic forms of As(III), As(V), Sb(III), Sb(V), Tl(I), and Tl(III) in river water samples is described.

A simple and rapid method for the simultaneous separation and determination of the inorganic ionic forms of As(III), As(V), Sb(III), Sb(V), Tl(I), and Tl(III) in river water samples is described. Analysis was performed using high performance liquid chromatography with inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (HPLC–ICP–MS). Gradient elution was applied with the use of two eluents of different composition. The total separation time was 16 min and limits of detection (LOD) were at the level of sub-micrograms per liter. The method was successfully applied for the simultaneous determination of arsenic, antimony, and thallium inorganic ions in river water.

Speciation analysis was first described in the literature in 1993 (1), and since then it has been demonstrated that it is not the total content of an element that has an impact on the environment, but its various chemical forms. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) describes speciation as the occurrence of an element in different chemical forms defined by the isotopic composition, electron configuration, oxidation state, oxidation complex, or molecular structure (2).

Although relatively expensive to undertake, speciation analysis is becoming more important. Speciation analysis is performed to study biochemical cycles of selected chemical compounds; determine toxicity and ecotoxicity of elements; ensure food and pharmaceutical quality control; and in technological process control and clinical analytics (3).

Toxicological data analyses requires the constant reduction in analyte detection limits to lower and lower concentrations, but many current methods do not provide analysts with the appropriate tools. For this reason, hyphenated methods can be used coupling chromatographic methods to spectroscopic detection (4,5). Hyphenated methods should be selective towards analytes of interest, sensitive over a broad concentration range, and should identify detected compounds. Hyphenated method selection should be directed by the analyte nature, possible method combinations, required sensitivity, and apparatus availability.

Speciation analyses are most often used for the determination of metals and metalloids (6); anthropogenic metalorganic pollution and its degradation products; inorganic disinfectant by-products (7); and speciation forms of platinum metal group, radionuclides, and rare earth metals (8). Among the many toxic metals and metalloid ions, special attention is given to elements such as arsenic, antimony, and thallium. Arsenic and antimony are elements characterized by complex physical and chemical properties and are of interest to both toxicologists and analytical chemists because of their toxicity, bioavailability, and reactivity. On the other hand, thallium is a poorly recognized element, even though its toxicity is higher than that of lead, mercury, or cadmium. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) classifies thallium as a priority pollutant. Priority pollutants rarely reach toxic concentrations in the environment, but their small toxic dose range and prevalence requires regulation. Monitoring of the elements antimony, arsenic, and thallium in the environment indicates contamination spread and changes in anthropogenic processes.

The combination of high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) or ion chromatography with mass spectrometry (MS) or inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP–MS) detection (9) provides a good range of sensitivity, and also qualitative and quantitative determination of various ionic forms of many elements, including the simultaneous determination of arsenic, selenium, and antimony species (10). To the best of our knowledge, there is only a very limited amount of data about thallium speciation using hyphenated techniques (11); no work about simultaneous separation and determination of inorganic species of arsenic, antimony, and thallium species has been published.

Experimental

Reagents

The following reagents were used to form standards: sodium arsenate(V) dibasic heptahydrate; sodium (meta)arsenite(III); potassium hexahydroxoantimonate(V); thallium(III) nitrate(V)trihydrate and anhydrous thallium(I) nitrate(V); ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt; and diethylenetriaminepentaacetic (all from Sigma-Aldrich). The antimony(III) standard solution (1000 mg/L), 65% nitric acid(V), and phthalic acid used in this study were from Merck. All the reagents had spectral purity. Calibration solutions were prepared by diluting an appropriate standard solution prepared from the suitable salt. All solutions and standards were prepared using high-purity deionized water (Milli-Q Gradient, Millipore) (<0.05 µS/cm).

HPLC

A 200 LC series speciation kit consisting of a Series 200 LC Peltier oven, a Series 200 LC autosampler, a Series 200 LC gradient pump, and a model 6100 Elan DRC-e ICP–MS detector was used (PerkinElmer). The analytical column was a 250 mm × 4 mm, 10-µm IonPac AS-7 column (Dionex).

The gradient elution program used two eluents: eluent A: 1.5 mM phthalic acid + 10 mM EDTANa2 (pH 4.5) and eluent B: 15 mM nitric acid + 2 mM DTPA. The elution program was as follows: 0–4 min, 100% eluent A; 4–12 min, 100% eluent B; and washing 4 min 100% by eluent A. The column temperature was 30 °C, and the injection volume was 150 µL. The ICP–MS detector parameters are shown in Table I.

Table I: ICP-MS detector parameters

Validation Procedure

The validation process of the method was based on the parameters of method precision, detection and quantification limits, analyte recovery, and method selectivity. To determine the repeatability of the method, spiked drinking water and river water samples were measured. Each of the four test series (n = 5) was preceded by a calibration of the instrument. The same solutions were also used for the determination of analyte recovery. Detection limits were calculated on the basis of determining the standard deviation of the calibration curves intercept obtained in the presented study. The quantification limit was determined as three times the detection limit.

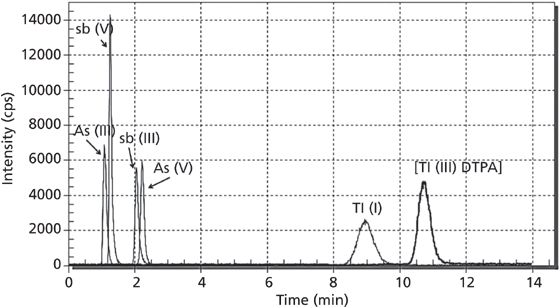

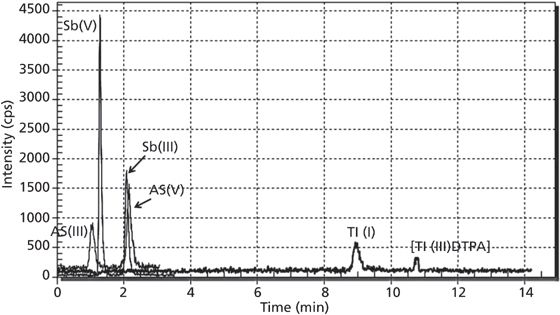

Figure 1: Synthetic water sample containing 10 µg/L of As(III), As(V), Sb(III), Sb(V), Tl(I), and Tl(III).

Results and Discussion

The developed method was characterized by high selectivity and low detection and quantification limits. Figure 1 presents the analysis of a synthetic water sample containing 10 µg/L of As(III), As(V), Sb(III), Sb(V), Tl(I), and Tl(III). Table II summarizes the method validation parameters. The repeatability and accuracy of the method (standard recovery) were therefore suitable for the analysis of trace amounts of inorganic species of arsenic, antimony, and thallium in water samples. Validation parameters were comparable with literature data (12–14), but it should be stated that these other studies have used other analytical methods and sample matrices (15,16). It is important to note that the main advantage of the developed method is the simultaneous separation and determination of inorganic species of arsenic, antimony, and thallium species in environmental water samples.

Table II: Method validation data

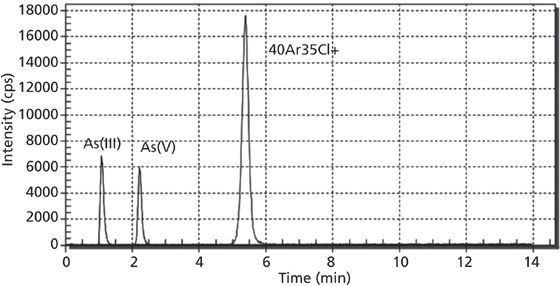

One issue encountered when performing the developed method is the various types of interferences, specifically As/ArCl interference. The mono-isotopic character of arsenic makes it impossible to remove by means of mathematical correction. Polyatomic individual 40Ar35Cl+ may cause peaks to interfere with 75As+. However, in optimized conditions, Cl- ions are eluted from the column after arsenic forms, as shown in Figure 2. This avoids such interferences because potentially interfering ions Ar35Cl+ are eluted between As(III)/As(V) and Tl(I)/Tl(III) ions at a retention time of around 5.5 min (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 2: Sample containing 10 µg/L As(III) and As(V).

Analysis of Real Samples

Samples of river water were collected from Upper Silesia District rivers (Poland) and analyzed by HPLC–ICP–MS. Analytes ions were found at the following concentrations ranges: As(III), 0.6–5.56 µg/L; As(V), 3.00–35.87 µg/L; Sb(III), 0.63–4.56 µg/L; Sb(V), 1.93–23.09 µg/L; Tl(I), 0.01–4.97 µg/L; and Tl(III), <0.01–0.10 µg/L. The rich sample matrices and high concentrations of chloride occurring in these rivers did not interfere with the analysis of samples as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Water sample from the Klodnica river in Silesia, Poland.

Conclusions

Even though speciation analysis has made enormous progress in the last 30 years, it is still a relatively new area of analytical chemistry. Its further development depends upon factors such as the development of new separation, detection, and sample preparation methods as well as the availability of new certified reference materials. Metals and metalloids ion determination and speciation have received significant attention in recent years because of their strong environmental impact. The proposed method could be a useful tool for fast and reliable determination of inorganic species of arsenic, antimony, and thallium.

HPLC–ICP–MS creates new and immense possibilities in speciation analysis. The main advantages of this technique are extremely low detection and quantification limits, insignificant interference influence, and high precision and repeatability of the determinations. Hyphenated methods also have their limitations, such as high price and apparatus complexity, and so are not in general laboratory use. The application of hyphenated methods requires a perfect understanding of analytical methods and apparatus. Those systems are expensive and often are used only in scientific research, rather than for routine analyses. Nevertheless, progress in the discussed method is becoming more and more important and visible as indicated by the number of applications (17).

References

(1) U. Forstner, Intern. J. Environ. Anal. Chem.51(2), 5–23 (1993).

(2) D.M. Templeton, F. Ariese, R. Cornelis, L.G. Danielsson, H. Muntau, H. Leeuwen, and R. ÅobiÅski, Pure Appl. Chem.72(1453), 1473–1470 (2000).

(3) A. Kot and J. NamieÅnik, Trends Anal. Chem.19(69), 69–79 (2000).

(4) R. Michalski, M. JabÅoÅska, and S. Szopa, in Speciation Studies in Soil, Sediment and Environmental Samples, Sezgin Bakirdere Eds., (Science Publishers/CRC Press/Taylor&Francis Group, 2013), pp. 242–262.

(5) M. Popp, S. Hann, and G. Koellensperger, Anal. Chim. Acta 668(114), 114–129 (2010).

(6) R. Michalski, M. Jablonska, S. Szopa, and A. Åyko, Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 41(133), 133–150 (2011).

(7) R. Michalski, LCGC Europe24(5), 18–23 (2011).

(8) C.C. May, P.J. Worsfold, and M.J. Keith-Roach, Trends Anal. Chem. 27(160), 160–168 (2008).

(9) R. Michalski, Current Trends in Mass Spectrometry,LCGC North America Suppl. S, 32–36 (2012).

(10) T. Lindemann, A. Prange, W. Dannecker, and B. Neidhart, Fr. J. Anal. Chem.364, 462–466 (1999).

(11) D. Nolan, E. Schaumlöffel, E. Lombi, L.Ouerdane, R. ÅobiÅski, and M. McLaughlin, J. Anal. Atom. Spectr.19, 757–761 (2004).

(12) B. KrasnodÄbska-OstrÄga, M. Asztemborska, J. Golimowski, and K. StrusiÅska, J. Anal. At. Spectr.23, 1632–1635 (2008).

(13) T. Lindemann, A. Prange, W. Dannecker, and B. Neidhart, Fr. J. Anal. Chem.368, 214–220 (2000).

(14) L.O. Iserte, A.F. Roig-Navarro, and F. Hernandez, Anal. Chim. Acta527, 97–104 (2004).

(15) T.I. Todorov, J.W. Ejnik, F.G. Mullick, and J.A. Centeno, Microchim. Acta151, 263–268 (2005).

(16) Y. Morita, T. Kobayashi, T. Kuroiwa, and T. Narukawa, Talanta73, 81–86 (2007).

(17) R. Michalski, M. Jablonska-Czapla, S. Szopa, and A. Åyko, in Encyclopedia of Analytical Chemistry, R.A. Meyers Ed., (J. Wiley, Chichester, UK, 2013) DOI: 10.1002/9780470027318.a9291.

Sebastian Szopa is a doctor of analytical chemistry at the Department of Chemistry of Silesian Technology University in Gliwice, Poland. He also works as an assistant at the Institute of Environmental Engineering, Polish Academy of Sciences. The scope of his responsibilities includes performing analysis of soil, soil-like materials, and ash using energy dispersive X-ray fluorescence (EDXRF); performing analysis of water and sewage using ICP–MS; and determining species of selected elements by using HPLC–ICP–MS.

Rajmund Michalski is an Associate Professor and the Deputy Director for Research at the Institute of Environmental Engineering, Polish Academy of Science in Zabrze, Poland. His current research interests include the application of IC, HPLC, and GC for the determination of inorganic and organic compounds in environmental samples, and the application of hyphenated techniques (IC–ICP–MS, IC–MS) in species analysis (water inorganic disinfection by-products, metal/metalloids ions). He has produced over 170 publications on the application of IC in environmental sample analysis.

Please direct correspondence to: rajmund.michalski@ipis.zabrze.pl

LIBS Illuminates the Hidden Health Risks of Indoor Welding and Soldering

April 23rd 2025A new dual-spectroscopy approach reveals real-time pollution threats in indoor workspaces. Chinese researchers have pioneered the use of laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS) and aerosol mass spectrometry to uncover and monitor harmful heavy metal and dust emissions from soldering and welding in real-time. These complementary tools offer a fast, accurate means to evaluate air quality threats in industrial and indoor environments—where people spend most of their time.

NIR Spectroscopy Explored as Sustainable Approach to Detecting Bovine Mastitis

April 23rd 2025A new study published in Applied Food Research demonstrates that near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) can effectively detect subclinical bovine mastitis in milk, offering a fast, non-invasive method to guide targeted antibiotic treatment and support sustainable dairy practices.