Analysis of Nicotine Alkaloids and Impurities in Liquids for e-Cigarettes by LC–MS, GC–MS, and ICP-MS

Special Issues

The purpose of this study was the development of various analytical MS methods to investigate the chemical composition of e-liquids used in electronic cigarettes and characterize their quality. Low-quality nicotine (the main active compound), glycerol, propylene glycol (solvents), or flavors could greatly increase the toxicity. The search of alkaloid contaminants of nicotine was performed by LC–MS-MS after a deep study of fragmentation pathways by high resolution ESI-MS. A fully validated method for quantitation of organic polar impurities such as cotinine, anabasine, myosmine, nornicotine, and N-nitroso-nornicotine and nicotine itself was developed using MS coupled to UHPLC. To evaluate organic volatile toxicants, headspace from e-cigarette refill liquids was sampled by SPME to perform GC–MS analysis. Finally, heavy metal residues as inorganic toxicants were determined by ICP-MS after simple dilution. A number of cases of contamination by metals (mainly arsenic) was detected.

The purpose of this study was the development of various analytical mass spectrometry (MS) methods to investigate the chemical composition of e-liquids used in electronic cigarettes and characterize their quality. Low-quality nicotine (the main active compound), glycerol, propylene glycol (solvents), or flavors could greatly increase the toxicity. The search of alkaloid contaminants of nicotine was performed by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS-MS) after a study of fragmentation pathways by high-resolution electrospray ionization (ESI)-MS. A fully validated method for quantitation of organic polar impurities such as cotinine, anabasine, myosmine, nornicotine, and N-nitroso-nornicotine and nicotine itself was developed using MS coupled to ultrahigh-pressure liquid chromatography (UHPLC). To evaluate organic volatile toxicants, the headspace from e-cigarette refill liquids was sampled by the purge-and-trap method to perform gas chromatography (GC)–MS analysis. Finally, heavy metal residues as inorganic toxicants were determined by inductively coupled plasma (ICP)-MS after simple dilution. A number of cases of contamination by metals (mainly arsenic) were detected.

The toxicity of e-cigarettes has not been completely clarified. They were introduced in the last 10 years to give smokers a healthier alternative to traditional cigarettes because of reduced burning (1,2). These devices, also known as electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) use a battery to generate a weakly heated aerosol based on polyalcohols, such as propylene glycol and glycerol with a small amount of water, containing pharmaceutical-grade nicotine. Many quantitation methods have been proposed for the study of ENDS components composition (3) and mass spectrometry (MS) techniques play a fundamental role in this context (4,5).

The purpose of this study was the development of various analytical MS methods to investigate the chemical composition of solutions used to fill e-cigarettes (e-liquids or e-juices) and characterize their quality, searching for toxicants. The main active principle of e-liquids is nicotine and ENDS are borderline products between pharmaceuticals and consumer goods (6). First of all, nicotine itself plays a key role in toxicity characterization and regulatory aspects. This alkaloid is generally obtained from tobacco and consequently some authors consider e-cigarettes to be tobacco products. On the other hand, the high concentration of purified nicotine in e-liquids assimilates e-cigarettes to medicinal products and accurate information about active principle quantity, purity, and risk is required. Liquid nicotine toxicity and management has been reviewed (7) and fatal consequences of improper use of e-liquids has been reported (8).

The diffusion of e-cigarettes in quite a different market from the pharmaceutical one claims for analytical methods that are able to individuate low-quality components. In particular, impurities and degradation products could be present or form in e-liquids even before e-cigarette operation and could increase their toxicity. It is not possible to characterize all of these compounds by a single MS technique because of the great chemical heterogeneity: an e-cigarette liquid sample contains polar and volatile organic compounds, metal ions, and more. The impurities that can contaminate the active principle (nicotine) could be its related alkaloids (9) such as anabasine, cotinine, myosmine, nornicotine, and its nitrosated derivative (NNN) a well-known carcinogenic compound (10,11). All of these compounds are known to be present in traces of tobacco and other plant parts from the Solanaceae family and may vary by different geographical origin (12). The solvents used for e-liquids to facilitate aerosol formation are polyalcohols. But some compounds belonging to this class display high toxicity-for example, diethylene glycol or ethylene glycol (further metabolized to oxalic acid)-and their presence must be avoided. Moreover residual solvents used for nicotine extraction and flavor stock solution could also be present as contaminants. In a similar way, some heavy metal elements could be present as simple pollutants or derive from industrial production and management of flavoring compounds and cosolvents. We developed some quantitative determination methods and applied known procedures to fully characterize as many classes of chemical toxicants as possible by MS. Samples from different producers were acquired in the Italian market.

To evaluate the greatest number of potential contaminants we had to use MS by coupling with different chromatographic and introduction techniques. The search for minor alkaloid and derivatives of nicotine was performed by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS-MS) after a deep study of fragmentation pathways by high-resolution electrospray ionization (ESI)-MS. To evaluate organic volatile toxicants, the headspace from e-cigarette refill liquids (e-liquids) was sampled by the purge-and-trap method to perform gas chromatography (GC)–MS analysis. Finally, heavy metal residues such as inorganic toxicants were determined by inductively coupled plasma (ICP)-MS after simple dilution.

Experimental

Chemicals and Materials

E-liquid samples were obtained from four different Italian industrial producers or importers (the products were manufactured in Italy, China, Poland, and Germany and are nonspecifically labeled as brands A, B, C, and D); all of them were solutions based on polyethylene glycol (60%), glycerol (30%), and water (10%) with various flavoring and five different nicotine declared concentrations (0, 9, 11, 16, and 18 mg/mL). LC–MS-grade acetonitrile was purchased from VWR (VWR International). Extrapure formic acid was obtained from Fluka (Sigma-Adrich). EPA/8260B (13) standard mix, nicotine, nicotine-D4, cotinine, anabasine, myosmine, nornicotine, N-nitrosonornicotine, chlorobenzene-D5, 1,4-dichlorobenzene-D4, fluorobenzene, methanol, trichloroacetic acid, heptafluorobutanoic acid, and ammonia were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich at a purity of ≥99%. High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-grade water was obtained from a MilliQ Academic water purification system (Millipore).

Sample Preparation

Samples for LC–MS analysis were prepared by diluting e-liquids in 95:5 (v/v) 5 mM heptafluorobutanoic acid and acetonitrile. Nicotine-D4 was added in methanolic solution to reach a final concentration of 100 ng/mL. For GC–MS, 50-µL e-liquid samples were diluted in 40 mL of water in a 40-mL gastight vial, adding the internal standard mixture (chlorobenzene-D5, 1,4-dichlorobenzene-D4, fluorobenzene at 0.5 ng/mL). Samples for ICP-MS analysis were prepared by simple dilution in ultrapure water. Then 100 µL of e-liquid was diluted to 10 mL to minimize matrix interferences.

High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry

A LTQ Orbitrap hybrid mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific), equipped with an ESI ion source, was used. The syringe pump effluent was delivered to the ion source at 10 µL/min, using nitrogen as both sheath and auxiliary gas. The source voltage was set to 4.5 kV. The heated capillary temperature was maintained at 275 °C. The acquisition method used had previously been optimized in the tuning sections for the parent compound (capillary, magnetic lenses, and collimating octapoles voltages) to achieve maximum sensitivity. The main tuning parameters adopted for the ESI source were 13 V for capillary voltage and 50 V for the tube lens. Full-scan spectra were acquired in the 50–700 m/z range. MSn spectra were acquired in the range between ion trap cut-off and precursor ion m/z values. Mass resolution was set to 30,000. Mass accuracy of recorded ions (versus calculated) was ±0.001 u (without internal calibration).

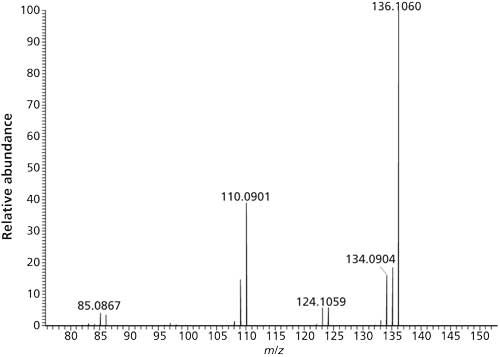

LC–MS

A Nexera LC-30AD (Shimadzu) ultrahigh-pressure liquid chromatography (UHPLC) instrument equipped with a 100 mm x 2.1 mm, 1.7-µm dp Kinetex C18 column (Phenomenex) was used to carry out the chromatography analysis. The eluents were acetonitrile (mobile-phase A) and 2.5 mM heptafluorobutanoic acid (mobile-phase B) in the following gradient conditions: 5–12% A in 7 min, 12–100% A in 1 min and re-equilibration. The injection volume was 5 µL, the flow rate was 500 µL/min, and the column was maintained at the temperature of 30 °C. A QTrap-5500 (Sciex) instrument, equipped with a Turbo Ion Spray source, was used to analyze samples. The source parameters were as follows: curtain gas, 25 (arbitrary units); gas 1, 20 (arbitrary units); gas 2, 30 (arbitrary units); temperature, 400 °C; ion spray voltage, 3500 V; declustering potential, 200 (arbitrary units); and entrance potential, 11 (arbitrary units). The detector was used in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode, and the transitions for each alkaloid are reported in Table I.

GC–MS

To detect and quantify volatile organic compounds (VOCs) a Varian Saturn 3900 system (Agilent) was used. The GC was equipped with a Tekmar purge-and-trap concentrator (operating on a 25-mL aqueous sample from gas-tight vials) and a Varian 1177 injector. For GC separation we used a 30 m x 0.25 mm Varian VF624 column in a temperature interval between 35 °C and 250 °C. The injector temperature was 170 °C and injection was done in splitless mode. Helium gas at 1.2 mL/min was used as carrier. The MS analyzer was a Varian Saturn 2100 ion-trap system with an EI source, and full-scan spectra were acquired in the 45–400 m/z range.

ICP-MS

Elemental ICP-MS determination was performed on an Agilent 7700 instrument with a quadrupole analyzer. Argon at 15 mL/min was used for plasma formation and at 1 L/min as the nebulizing gas. The RF power was 1.55 kW, and the RF matching was set at 1.80 V. Samples were introduced using a peristaltic flow at 250 µL/min.

The analytical quantitative determination, after building a calibration curve over seven concentration levels, involved boron, chromium, nickel, cobalt, copper, silver, arsenic, manganese, cadmium, antimony, barium, aluminum, iron, and zinc. Yttrium, iridium, terbium, and scandium were used as internal standards.

Results and Discussion

Nicotine-Related Alkaloids: High-Resolution MS-MS Study

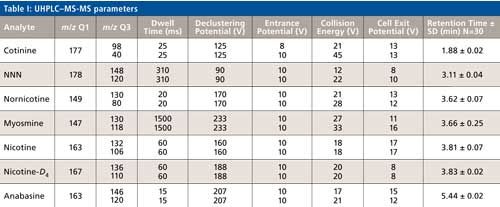

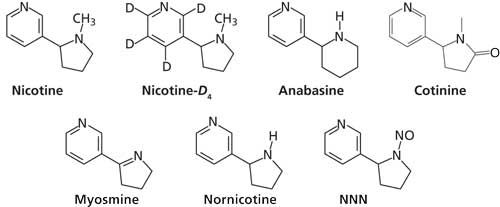

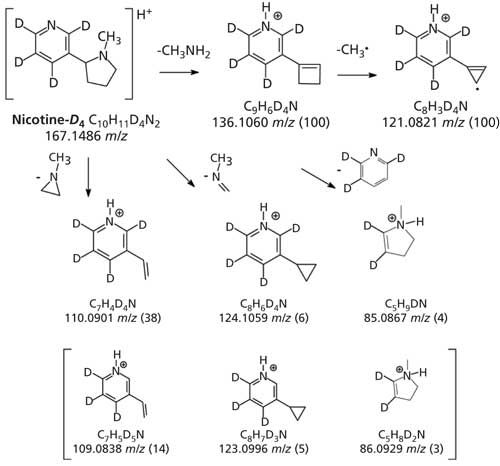

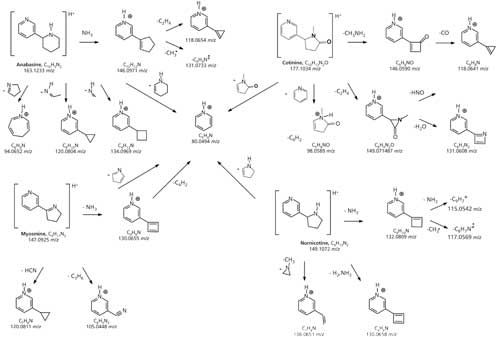

Nicotine and related alkaloids subjected to the study are reported in Figure 1. The structures based on high-resolution MSn of the studied ions were hypothesized to clarify fragmentation pathways with the aim to optimize the selection of product ions for the following quantitative analysis by UHPLC–MS. The fragmentation of nicotine and some related alkaloids was described (14), but their spectra share several ions and it was not simple to determinate some molecules selectively (especially if they are isobars such as nicotine and anabasine). At first we investigated the fragmentation pathways of the compounds generally analyzed in biological samples, nicotine and its main metabolite cotinine. To evidence the mechanism of fragmentation, high-resolution MSn of tetradeutero nicotine (nicotine-D4) is shown in Figure 2. Figure 3 displays its high-resolution MS2 spectrum. The chief fragmentation pathway proceeds with elimination of methylamine without involvement of pyridine deuterium atoms. A particular MS3 fragmentation based on methyl radical elimination was observed. Because this behavior does not agree with the one reported in literature (14) (loss of hydrogen) we also checked undeuterated nicotine to confirm the methyl loss.

Figure 1: Structures of the studied alkaloids.

Secondary fragmentation pathways, because of the loss of methylaziridine, methylamine, and pyridine showed evidence of a significant grade of hydrogen scrambling (Figure 2).

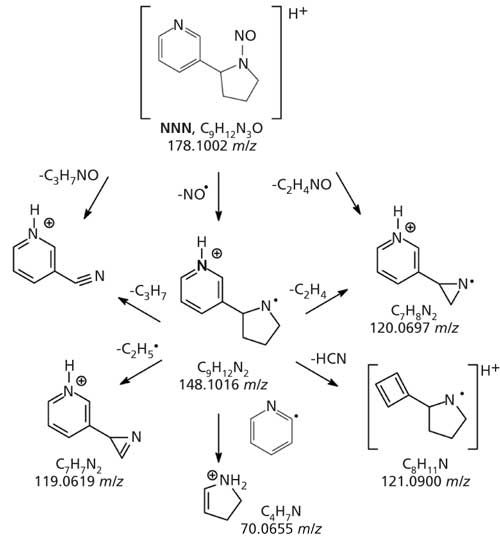

Figure 2: NNN MH+ HRMSn proposed fragmentation pathways.

Figure 3: High resolution MS2 spectrum of nicotine-D4.

The most intense high-resolution MSn pathways of other nicotine-related alkaloids are reported in Figure 4. It is noteworthy that some apparently common ions are in fact isobaric by nominal mass, but own a different elemental composition only resolved by the use of high-resolution analyzers. For all of the investigated compounds, the pyridine ring is less prone to fragment and the elimination of small molecules containing nitrogen of pyrrole moiety represent the favorite way of fragmentation. The only circumstance where homolytic bond breaking is significant is the case of the nitroso derivative NNN. The scheme of high-resolution MSn spectra generation of NNN is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 4: Anabasine, myosmine, and nornicotine MH+ high-resolution MSn proposed fragmentation pathways, evidencing common fragmentations and isobaric losses with different elemental composition.

Figure 5: NNN MH+ high-resolution MSn proposed fragmentation pathways.

UHPLC–MS-MS Analytical Method Validation

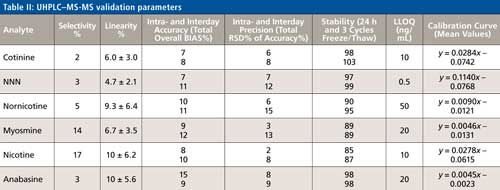

Knowledge of mass fragmentation behavior allowed us to develop a liquid chromatographic method that was able to distinguish and selectively evaluate nicotine and related alkaloids in a typical e-liquid matrix (60% ethylene glycol, 30% glycerol, 10% water). Precursor and product ions were chosen to guarantee minimum interferences. MRM parameters and retention times are reported in Table I. For each alkaloid, the following validation parameters were evaluated in accordance with the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines (15): the selectivity (versus matrix and for each analyte versus the standard mixture of the other six molecules, including internal standard), the linearity of calibration curve, the intra and inter day accuracy and precision, the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ), and the short term stability (up to 24 h and after three cycles of freeze and thaw) of the analyzed samples. The calibration curves were obtained in a range of 10–750 ng/mL, using 10-, 50-, 100-, 500-, and 750-ng/mL combined standards solutions. All of these parameters are reported in Table II and are in good agreement with the FDA guideline limits. Definitions and details for calculation are described in a previously reported validation protocol (16). Linearity parameters were fully observed; selectivity was <20% in all of the cases, intrarun repeatability was between 3% and 14%; inter-run repeatability was between 5% and 20%; precision (relative standard deviation [RSD]% of accuracy%) was <13%. A room temperature stability of 24 h was ascertained for the studied analytical solutions. LLOQ values were in the 0.5–20 ng/mL range and recovery for all analytes was 98%.

The developed method is fast (the total analysis time was 16 min including re-equilibration), reliable, and, after proper dilution of e-liquid samples, allows highly sensitive determination of nitrogenous impurities of nicotine.

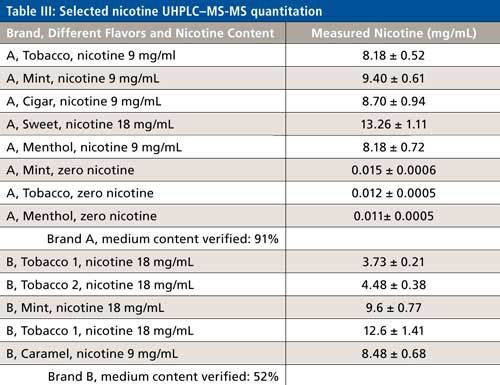

UHPLC–MS-MS Analytical Results

Using the developed UHPLC–MS-MS method, we analyzed e-liquid samples from different producers to evaluate nicotine title and search for the presence of impurities. The nicotine concentration in examined samples strongly disagrees from the declared quantity (in some samples nicotine is only 20% with respect to the stated quantity: see selected results in Table III). This could be a big issue for the so-called vapers and underlines the requirement of more-strict standards in quality control of e-liquid manufacturing. We did not find significant presence of any of the searched impurities over the limit of 0.3% compared to nicotine. This is in agreement with the declared use of pharmaceutical-grade active principle by the producers. Nicotine itself has been rather identified in samples where instead it should have been absent, probably because of mismanagement of the production and packaging facilities.

GC–MS Analytical Results

We searched for toxic glycols and semi-volatile organic components of added flavors by direct injection of methanol solutions of e-liquids (data not shown), but the raw materials used were of good quality and no contamination was detected.

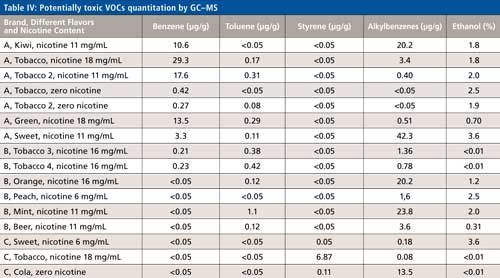

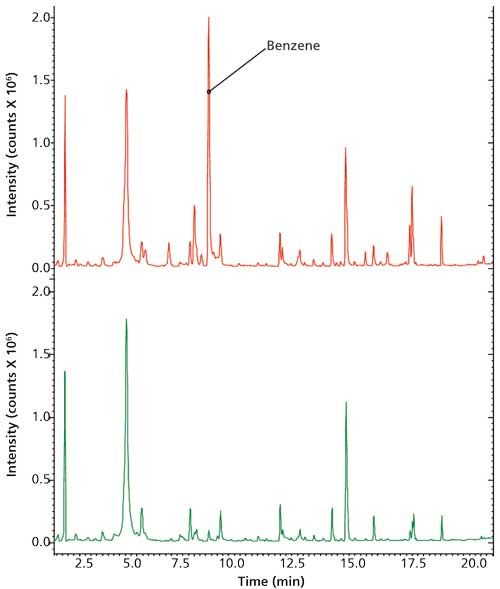

By analyzing the VOC fraction, we could conversely observe significant organic solvent contamination in a number of cases. We operate in agreement with Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Method 8260 (13), using the water-diluted e-liquid solution as a model of vaped aerosol dispersion in the oral cavity. Table IV lists some findings that are noteworthy from the toxicological point of view. Carbonyls were not reported in this article because they could form by thermal degradation of glycols and will be the subject of a future publication. Benzene, styrene, alkylbenzenes (ethylbenzene, n-propylbenzene, isopropylbenzene, sec- and tert-butylbenzene, 1,2,4- and 1,3,5-trimethylbenzene, isopropyltoluene, o-, m- and p-xylene), and ethanol were detected. These impurities could be linked to low-quality nicotine extraction solvents used. This was confirmed by one circumstance (a set of similar products imported from a single producer, Table IV, brand A) where the benzene quantity is directly related to the presence of nicotine.

ICP-MS Analytical Results

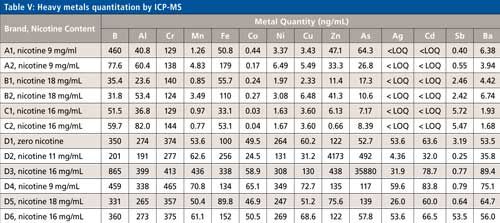

We quantified 14 different metal and semi-metal elements on diluted water solution of various e-liquid samples by ICP-MS. Normally, heavy metals are not significant pollutants of e-liquids and their presence is generally acknowledged not to be higher than 0.2 mg/L (19). Since reference values for risk management are referred to drinking water, these data seem to suggest that metals are of little or no concern in evaluating e-cigarette sources of toxicity. A selection of results is reported in Table V. All of the data are in agreement with previous reports with the exception of strong contaminated “outlier” samples such as e-juice D3. In particular, arsenic high concentration, even if classifiable as spot contamination, drives the attention on the importance of quality controls to avoid unexpected harming or toxic effects.

Figure 6: VOCs GC–MS chromatogram showing evidence of benzene contamination.

Conclusions

In our work, fragmentation pathways of nicotine-related impurities were elucidated using high-resolution mass spectrometry. With the information we obtained, a selective UHPLC–MS-MS multianalyte method was developed for the quantitative determination of nicotine and related alkaloids in the classical e-cigarette refill liquid matrix. The method was completely and successfully validated following FDA guidelines. We analyzed several e-liquids from different producers in Italy, China, Poland, and Germany. The nicotine concentration in the analyzed samples did not result in compliant declared values. We found differences between declared and actual concentrations ranging from -70% to +20%. This has been observed by other authors too (17,18), indicating that it is a common problem in the e-cigarette market. No sample contained nitrosamines at levels above the limit of detection nor any common nicotine impurities above 0.3% of nicotine itself. By analyzing the VOC fraction and metals we could observe significant contamination by benzene, styrene ethanol, and even arsenic in a number of circumstances. Finally, this study highlights the fundamental role of different MS analyzers in the characterization of sources of potential toxicity by chemically heterogeneous compounds in a atypical matrix.

References

- I.L. Chen, Nicot. Tob. Res.15, 615–616 (2013).

- M.R. Gualano, S. Passi, F. Bert, G. La Torre, G. Scaioli, and R. Siliquini, J. Public Health37, 488–497 (2015).

- V. Bansal and K.H. Kim, Trends Anal. Chem.78, 120–133 (2016).

- K.B. Scheidweiler, D.M. Shakleya, and M.A. Huestis, Clin. Chim. Acta413, 978–984 (2012).

- B.M. da Fonseca, I.E.D. Moreno, A.R. Magalhães, M. Barroso, J.A. Quiroz, S. Ravara, J. Calheiros, and E. Gallardo, J. Chrom. B889–890, 116–122 (2012).

- K.E. Farsalinos and J. Le Houezec, Risk Manag. Healthc Policy8, 157–167 (2015).

- J. Won Kim and C.R. Baum, Pediatr. Emerg. Care31, 517–521 (2015).

- S. Bartschat, K. Mercer-Chalmers-Bender, J. Beike, M.A. Rothschild, and M. Jübner, Int. J. Legal Med.129, 481–486 (2015)

- L.Q. Sheng, L. Ding, H.W. Tong, G.P. Yong, X.Z. Zhou, and S.M. Liu, Chromatographia62, 63–68 (2005).

- I. Stepanov, S.G. Carmella, A. Briggs, L. Hertsgaard, B. Lindgren, D. Hatsukami, and S.S. Hecht, Cancer Res.69, 8236–8240 (2009).

- H.J. Kim and H.S. Shin, J. Chrom. A1291, 48–55 (2013).

- L. Zhang, X. Wang, J. Guo, Q. Xia, G. Zhao, H. Zhou, and F. Xie, J. Agric. Food Chem.61, 2597–2605 (2013).

- Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs): SW-846 Method 8260 (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C., Method 8260B, 1996). Available at: https://www.epa.gov/quality/volatile-organic-compounds-vocs-sw-846-method-8260.

- T.J. Smyth, V.N. Ramachandran, A. McGuigan, J. Hopps, and W.F. Smyth, Rapid Comm. Mass Spec.21, 557–566 (2007).

- US Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), Guidance for Industry Bioanalytical Method Validation. (FDA, Rockville, Maryland, 2001). Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM070107.pdf.

- F. Dal Bello, V. Santoro, V. Scarpino, C. Martano, R. Aigotti, A. Chiappa, E. Davoli, and C. Medana, Drug Test. Analysis. doi:10.1002/dta.1827 (2015).

- M.L. Goniewicz, T. Kuma, M. Gawron, J. Knysak, and L. Kosmider. Nicot, Tobacco Res.15, 158–166 (2013).

- P. Kubica, A. Kot-Wasik, A. Wasik, and J. Namiesnik, J. Chrom. A1289, 13–18 (2013).

- M.L. Goniewicz, J.Knysak, M. Gawron, L. Kosmider, A. Sobczak, J. Kurek, A. Prokopowicz, M. Jablonska-Czapla, C. Rosik-Dulewska, C. Havel, P. III Jacob, and N. Benowitz, Tob. Control23, 133–139 (2014).

Claudio Medana, Riccardo Aigotti, Cecilia Sala, Federica Dal Bello, Valentina Santoro, Daniela Gastaldi, and Claudio Baiocchi are with the Department of Molecular Biotechnology and Health Sciences at the Università degli Studi di Torino in Torino, Italy. Direct correspondence to: claudio.medana@unito.it

High-Speed Laser MS for Precise, Prep-Free Environmental Particle Tracking

April 21st 2025Scientists at Oak Ridge National Laboratory have demonstrated that a fast, laser-based mass spectrometry method—LA-ICP-TOF-MS—can accurately detect and identify airborne environmental particles, including toxic metal particles like ruthenium, without the need for complex sample preparation. The work offers a breakthrough in rapid, high-resolution analysis of environmental pollutants.

The Fundamental Role of Advanced Hyphenated Techniques in Lithium-Ion Battery Research

December 4th 2024Spectroscopy spoke with Uwe Karst, a full professor at the University of Münster in the Institute of Inorganic and Analytical Chemistry, to discuss his research on hyphenated analytical techniques in battery research.

Mass Spectrometry for Forensic Analysis: An Interview with Glen Jackson

November 27th 2024As part of “The Future of Forensic Analysis” content series, Spectroscopy sat down with Glen P. Jackson of West Virginia University to talk about the historical development of mass spectrometry in forensic analysis.

Revealing the Ancient Secrets of Chinese Swamp Cypress Using Cutting-Edge Pyrolysis Technology

November 18th 2024A study published in the Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis by Yuanwen Kuang and colleagues used advanced pyrolysis techniques to reveal the preservation and chemical transformations of 2,000-year-old Chinese swamp cypress wood, offering valuable insights for archaeological conservation and environmental reconstructions.